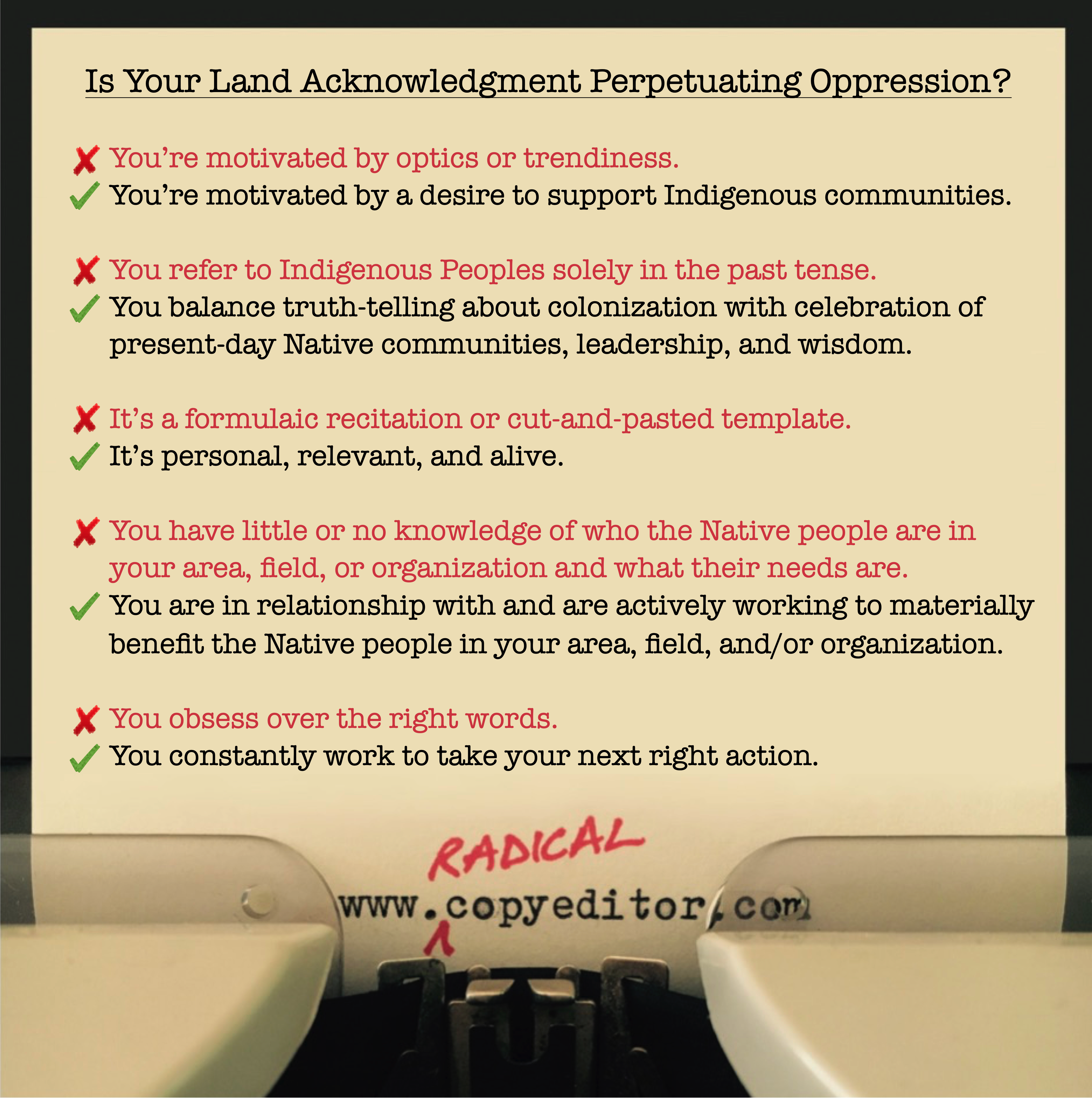

Okay, friends. Let’s talk about land acknowledgments.

For those who are unfamiliar, a land acknowledgment is most often understood as a verbal or written recognition of the original Indigenous nations whose lands are being occupied by a person, group, event, school, or other organization.

In recent years, land acknowledgments have become more and more common among people, groups, and organizations with a progressive or social justice-seeking orientation. You can find them written in website footers, displayed on physical plaques and signs, spoken at the start of everything from sports games to plays to academic conferences to work meetings, included in folks’ Zoom names or at the bottom of email signatures, and in hundreds of other places.

It’s a powerful practice, but it can go sideways really easily, a truth that is constantly pointed out by Native folks. So let’s get into it.

Continue reading “How to Ensure that Your Land Acknowledgment Doesn’t Perpetuate Oppression”