This quirky, mighty word carries so much meaning. Self-identity, umbrella term, academic discipline, political orientation, verb, and—yes—slur.

Yet more than three decades after a fundamental shift in what this word communicates, the mainstream still resists acknowledging the fullness of what queer means. What’s this resistance to queer really about? And how should this complexity be navigated?

Let’s start from the beginning.

A brief history of queer

Etymologists aren’t sure of the roots of the word queer. Some think it made its way into English via the German word quer (oblique, across, perverse). Others theorize that it arrived by way of the Middle Irish word cúar (curved, bent, crooked). Regardless, queer dates back to the early 1500s, first spotted in print in Scotland. For four hundred years the word was used to mean strange, odd, peculiar, eccentric, disreputable, suspicious, and/or dubious—with no sexual connotation.

The first known use of queer to refer to same-sex desire in print was in 1894 when John Douglas, a Scot with the ironic title Marquess of Queensberry, blamed “Snob Queers” for corrupting his sons—one of whom was rumored to have been sexually involved with Britain’s prime minister, and another of whom was Oscar Wilde’s lover. Given the media coverage of Wilde’s subsequent trial (at which Douglas’s epithet was read aloud), it’s no wonder that queer began taking on this meaning more widely.

However, queer wasn’t just used as a disparaging term for people (usually men) with same-sex desires; it was also used as a self-identity term, and it was slipped into novels and other writings by authors such as Gertrude Stein to intentionally carry a double meaning.

In his book Gay New York, historian George Chauncey documents how queer and fairy were used as within-community identity terms in the early 1900s. Fascinatingly, fairy meant a flamboyant, effeminate man, while queer was used by stereotypically masculine men. Men whose homosexuality involved gender deviance called themselves fairies, whereas men whose homosexuality was solely about sexual attraction called themselves queers. Of course, the mainstream world was oblivious to these nuances and used queer to refer to all homosexual men (and occasionally women), as well as stereotyping all of them as flamboyantly feminine.

In the 1920s, the word gay first started being used as a within-community code word. Chauncey reports that although such use began among the “fairies,” by 1940 gay had supplanted queer in New York, becoming the dominant word used by all homosexual men, particularly as younger folks associated queer with the derogatory flavor the mainstream had assigned to it, of deviance, abnormality, and perversion. Throughout the ’40s and ’50s the use of gay increased, and it was eventually used by women as well as men—but it was still a within-community term; in formal contexts the word homosexual was used.

Meanwhile, as noted by historical sociologist Jeffrey Weeks, queer continued to be the dominant term used in many places, such as Britain: “By the 1950s and 1960s to say ‘I am queer’ was to tell of who and what you were, and how you positioned yourself in relation to the dominant, ‘normal’ society. … It signaled the general perception of same-sex desire as something eccentric, strange, abnormal, and perverse.”

It wasn’t until after the Stonewall Uprising that gay became a mainstream word. According to historian Rictor Norton, in early 1969 there were fifty homosexual or homophile organizations in the United States, but the formation of the Gay Liberation Front directly after Stonewall spurred two hundred other gay organizations by the end of 1970; three years later there were more than a thousand gay and lesbian organizations across the country. The word gay also started being used in English-speaking and non-English-speaking nations around the world.

Assimilation versus anti-assimilation

In order to understand the linguistic revolution around the word queer that happened next, we have to chart another essential feature of the LGBTQ landscape: the ideological divide between assimilationists and anti-assimilationists.

Ever since individuals started to form community as same-gender-loving people more than a century ago, there has been a push-pull dynamic between those who want to blend in with the mainstream and those who want to wildly redecorate the whole world. For example, the early self-described queers discussed above saw themselves as “normal” men who just happened to be attracted to other men. Chauncey noted that these men tended to be more middle class and had more to lose if they were perceived as gender nonconforming, so they often shunned visibly gender defiant effeminate fairies—who, by contrast, had no interest in blending in; they were out to subvert the rules of gender and sexuality.

It’s completely understandable that so many people want to blend in and assimilate into “normal” society. But in general, key LGBTQ activism over the years—at least in the United States—has been launched by anti-assimilationists and subsequently taken over and redirected by assimilationists, largely because as a group they tend to have closer proximity to privilege and power. It’s easier to believe in the possibility—and inherent value—of assimilation into normalcy if you are only oppressed in one or two ways (e.g., being gay but also white, cisgender, nondisabled, and middle class) than if you are oppressed in many ways (e.g., being trans, Black, disabled, and poor).

For example, the virulently anti-homosexual U.S. political climate of 1950 led to the founding of the Mattachine Society, the biggest U.S. gay rights organization of the mid-twentieth century, by radical communist and labor activist Henry Hay, who saw homosexuals as a distinct and potentially militant cultural minority and envisioned Mattachine as fighting for “the whole mass of social variants.” But within three years, as documented by Learned Foote, Mattachine saw an influx of politically conservative middle-class white members who took over the leadership of the organization and redirected its goals in the direction of helping homosexuals integrate into mainstream society.

Similarly, after increasing policing and criminalization of gender variance and gay social spaces came to a head with Stonewall, the explosion of activism that followed focused on fighting police brutality and claiming sexual public space. Yet as this activism moved from the streets into funded organizations over the following decade, the focus became a comparatively politically conservative quest for access and equality via the criminal-legal system, government, military, and so forth, rather than challenging the fundamental inequalities inherent in such institutions.

What happened next changed everything: the AIDS crisis. By 1985, the epidemic had killed 40,000 people in the United States, yet President Ronald Reagan had not even deigned to name it publicly, much less dedicate funding to it. Meanwhile, as discussed by sociologist Deborah Gould in her book Moving Politics, major gay and lesbian organizations didn’t want to be associated with AIDS, out of fear of being further marginalized by mainstream media. Their primary political tactic was to work toward positive visibility via media and lobbying and show that gay people were just like everyone else, a tactic that was increasingly ineffective in the face of rising political conservatism, religious fundamentalism, and AIDS stigma.

The queer revolution

AIDS activists were clear: the dominant gay rhetoric of tolerance and the goal of assimilation into normalcy was meaningless when so many of them were sick and dying and being alternately ignored, blamed, and damned by mainstream culture. It was time for radical goals, radical action, and radical language.

So they started ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and three years later the spin-off group Queer Nation, which had a broader focus than AIDS. Their methods were confrontational, direct action, forcing the powerful to pay attention, fighting for agency for people with HIV/AIDS. To them, the word gay, which had embodied a revolutionary spirit in the wake of Stonewall, now spoke of middle-class white men whose highest aspiration was being accepted into mainstream white society. This word could not hold their rage, their needs, or their reality. But there was another word that could.

In June 1990, activists handed out leaflets at the New York Pride parade emblazoned with the words “QUEERS READ THIS.” Front and center appeared the following declaration:

Being queer is not about a right to privacy; it is about the freedom to be public, to just be who we are. It means everyday fighting oppression; homophobia, racism, misogyny, the bigotry of religious hypocrites and our own self-hatred. … Being queer means leading a different sort of life. It’s not about the mainstream, profit-margins, patriotism, patriarchy or being assimilated. It’s not about executive directors, privilege and elitism. It’s about being on the margins, defining ourselves; it’s about gender-fuck and secrets, what’s beneath the belt and deep inside the heart.

Queer was the perfect word for the moment. The in-your-face, defiant reappropriation of this pejorative term turned it on its head; its meanings of abnormality and perversion were intentionally taken on and reforged into pride in being different and rejection of the status quo. So-called queer bashers had used queer as a tool of shame, exclusion, and punishment for not conforming to sexual and gender norms. Their targets now turned this same tool into one for fighting homophobia, deriding and upending normalcy, and celebrating noncompliance.

AIDS activists weren’t the first to use queer in this manner; in fact, prominent New Left activist Paul Goodman published an essay in 1969, revised in 1977 under the title “The Politics of Being Queer,” that was a clear precursor. But under the influence of Queer Nation, queer “shifted from being a negative, individualizing description to a signifier of collective agency and militancy,” in the words of Jeffrey Weeks. “Rather than being a sign of internalized homophobia, queer highlights homophobia in order to fight it,” explained linguist Robin Brontsema. And as Jeffrey Escoffier and Allan Bérubé reflected at the time, “Queer is meant to be confrontational—opposed to gay assimilationists and straight oppressors while inclusive of people who have been marginalized by anyone in power.”

A tectonic shift in language had occurred. Queer was something unique—rather than being a sexual orientation that kept people in discrete identity boxes, queer was a political orientation that set out to destroy boxes. Queer simultaneously spoke to (a) the need for a word that transcended binary, essentialist beliefs about sexuality and gender and embraced fluidity, (b) coalition across lines of difference, particularly race, class, and gender, and (c) a revolutionary rather than reformist approach to the status quo and societal institutions like government, police, and prisons.

The richness of this word and its meanings also meant that it leapt from activism into other areas—most notably, the academy. By 1993, queer theory had fully emerged as a completely new field of study, building on post-structuralism and feminist theory. Queer theory holds that truth is subjective, that sexuality and gender are socially constructed rather than completely hardwired, and that sexuality, gender, race, class, dis/ability, age, and other aspects of identity are deeply entangled. To queer something, under queer theory, is to interpret it in a way that upends norms of gender and sexuality. So queer’s new meanings now existed in noun, adjective, and verb form!

We’re here, we’re queer, but y’all ain’t used to it

The power of queer lies in the fact that this word can never be fully domesticated. Its meanings and usages can shift and broaden, but it will always have an edge; it will never be a word that is neat, tidy, or comfortable for all who encounter it.

Mind you, that’s not for lack of trying! As queer gained steam throughout the 1990s, it was used in a variety of ways and contexts, some of which attempted to neutralize its radical meanings. Robin Brontsema noted four major uses of queer in 2004, fifteen years after its shift in meaning:

- by queer folks as a self-identity term that contested the boundaries of gay and lesbian and described anyone with a non-normative sexual identity or practice;

- by non-queer gay men and lesbians as a replacement for LGBT that in practice tended to continue disregarding bisexuals and trans people;

- by popular television (e.g., Queer as Folk and Queer Eye for the Straight Guy) as a “trendy, hip replacement of gay” that wasn’t even inclusive of women; and

- by bigots as hate speech.

This shows that queer had maintained its primary, radical meaning, but it was also being worn down by the forces of the status quo to mean, broadly, “not straight.” Of course, if a word gets used to mean “not straight,” it will be interpreted by a lot of people as simply referring to the stereotypical, most visible segment of people who aren’t straight: gay white men—which is pretty ironic.

But queer, true to its nature, refused to be assimilated. Many people objected to being called queer—some because they felt the word was a permanently violent one, some because they disliked the politics that queer represented, many because of both. At the same time, more people than ever before were using queer to describe themselves—a large population that was difficult to write off.

This resulted in many well-meaning people avoiding queer entirely, even while the word increasingly became an undeniable and unavoidable feature of the landscape of sexuality and gender. This tug of war can be seen in the fact that by 2010 the initialism LGBTQ had begun to overtake LGBT in many places as the most common way to refer to everyone who isn’t straight and cisgender—yet many people have problematically insisted that the Q means questioning, a trend that never would have happened without intense resistance to queer.

Meanwhile, most dictionaries didn’t acknowledge any shift in queer, which had the effect of giving credence to those who argued against ever using the word, since the age-old definition of queer was (a) odd or peculiar and (b) homosexual (disparaging + offensive). Even as major English dictionaries finally began, in far-too-limited ways, to acknowledge the primary present-day use of this word, they continued to include inaccurate notes such as “still chiefly a slang term of contempt or derision” (Webster’s New World College Dictionary, 5th edition, 2014).

The hallowed Oxford English Dictionary only added the modern-day definition “denoting or relating to a sexual or gender identity that does not correspond to established ideas of sexuality and gender, especially heterosexual norms” in December 2016 (replacing the text “of or relating to homosexuals or homosexuality”), and Merriam-Webster’s similarly outdated entry was only updated in 2019.

The radical copyeditor’s approach to queer

So how should queer be used by those who seek to use language consciously and caringly?

First of all, it’s time to dispel the myth that only queer people can use the word queer. Queer is not primarily about who says it but about what it’s used to communicate. It is essential that non-queer people understand what this word means today and use it to communicate those meanings.

Second, if you don’t want to use the word queer to describe yourself, by all means, don’t. But when people categorically avoid the word queer in any context, even if their intention is to respect those who hate the word, the impact is rejection of everything that queer stands for (i.e., challenging the status quo, upending dominant norms of sexuality and gender, and solidarity among all those who are oppressed). Ignoring queer also buys into the mythology that there are no meaningful differences among people who aren’t straight.

This doesn’t mean queer shouldn’t be used with care. It should—but not for the reasons people usually name. Here are the radical copyeditor’s dos and don’ts.

DO use queer in reference to people who describe themselves as queer. Recognize queer as a valid identity.

My sexual orientation is queer. To me, this means I’m attracted to people of many genders, but more importantly it means that my sexuality actively challenges norms and consciously informs my radical politics. My gender identity is genderqueer. To me, this means that who I am actively queers gender: my experience and expression of gender actively subvert gender norms. There are no other words that fully communicate who I am. And I’m not alone: more U.S. trans people identify as queer than any other sexual orientation, according to the 2015 U.S. Trans Survey.

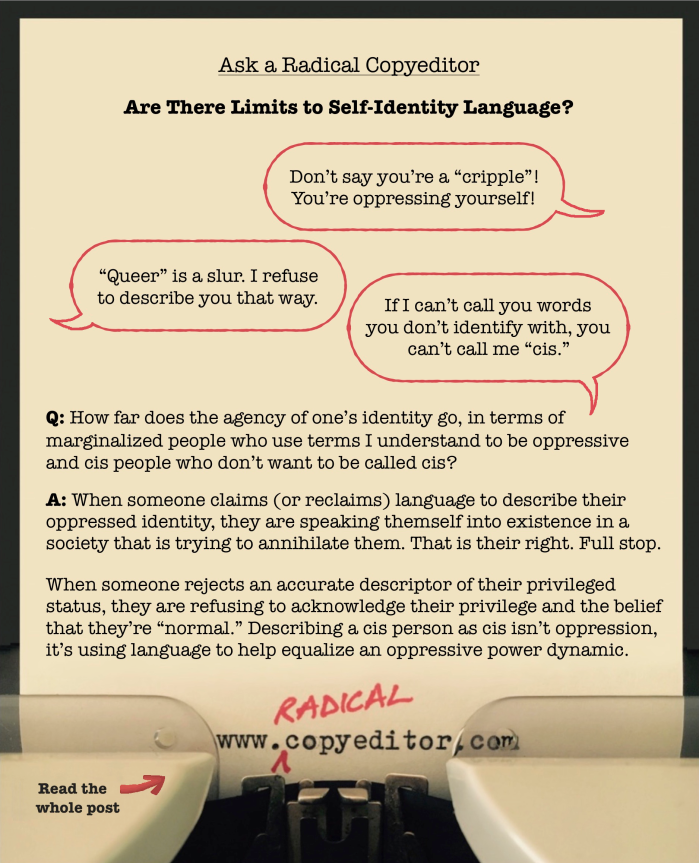

My partner, who is also queer, has had well-meaning strangers tell him, “Oh, don’t call yourself that!” and has had editors attempt to neutralize his bio by changing “queer activist” to “LGBT activist.” An older white lesbian colleague once described me as “an LGBT person who identifies as queer.” It is never okay to “correct” the language that people use to describe themselves. I’m not a gay or lesbian or bi person who calls myself queer; I’m a queer person. Queer needs to be respected as a legitimate identity, included as an option on surveys that ask about sexual orientation, and rightly defined as the Q in LGBTQ.

DO use queer in reference to people and things that are aligned with the politics of queerness.

In its simplest form, queer means upending mainstream norms about sexuality and gender (particularly the ones that say that being straight is the human default and that gender and sexuality are hardwired, binary, and fixed rather than socially constructed, infinite, and fluid). It also usually speaks to solidarity across lines of race, class, dis/ability, gender, sexuality, and other identities as part of a radical politics of transforming the status quo and working toward collective liberation.

So scholarly fields like queer theory, queer studies, and queer theology are designed to queer their topic of focus, be it philosophy, literature, film, religion, history, or any number of other things—meaning they interpret things in a way that upends norms of gender and sexuality and engage with how race, class, dis/ability, gender, sexuality, and other identities intersect with and affect each other. Queer activism, queer politics, and queer organizations do the same. It’s important to acknowledge and honor queer politics and queer as a verb by using it in this manner.

DO use queer to describe groups, communities, and movements who resist gender/sexual norms in diverse and mutually supportive ways.

One of the key ways that queer has been used since its shift in meaning has been as a label that stands for difference rather than sameness. For instance, an early-’90s leaflet distributed by Philadelphia’s Queer Nation chapter described queers as:

Lesbians, gay men, bisexuals and homosexuals, transsexuals, transvestites, ambi-sexuals, effeminate men and masculine women, gender-benders, drag queens, bull dykes and cross dressers, lezzies, diesels and bruisers, marys and faeries, faggots, buggers, hairy pit-bulls, butches and fems.

Similarly, at a 1991 conference, “queer community” was described as “the oxymoronic community of difference” of people of all sexualities, genders, races, disabilities, classes, and political persuasions, where “difference from the norm is about all that many people … have in common with each other.”

This use of queer has continued to this day, as a way of speaking not only to the incredible diversity of people who defy or deviate from sexual and gender norms but also to solidarity between these folks—celebrating our differences and supporting and fighting for each other. In the words of Shiloh Morrison, “Queer isn’t about who you fuck, it’s about who you are accountable to.”

The concept of queer as an umbrella term refers to this use. But it’s not an umbrella for everyone who isn’t cis and straight; rather, it’s an umbrella for everyone whose resistance to gender/sexual norms leads them to align themselves with other gender/sexual outlaws and outsiders.

DON’T use queer as a synonym for gay or to refer to non-queer LGBT people.

If you’ve made it this far, hopefully it’s clear by now that queer and gay are not interchangeable. Queer isn’t shorthand or a hip way to avoid a long list of identities; it has a unique meaning, one that’s about subverting norms and challenging the status quo. So don’t use queer as a shortcut, don’t use it to refer to people who actively don’t identify with it, and don’t use it to refer to LGBT people who don’t believe in what queer stands for, such as affluent assimilationist gay men, anti-trans lesbian separatists, and trans Trump-lovers. (See, for example, Pete Buttigieg, who is undeniably gay but absolutely not queer.)

DON’T use queer pejoratively.

Queer is still sometimes used as a violent slur. Definitely don’t do this.

That said, it’s important to remember that what makes a word a slur is its usage and context. No word means the same thing to all people in all contexts. Respecting self-identity language is essential; this means not calling people queer if they don’t want to be referred to that way and calling people queer if that’s how they describe themselves. Both are equally important.

In conclusion

Queer is deeply complex and beautifully multifaceted. It’s not an inherently violent word, even if it has been used in harmful ways. In today’s world, queer is used to communicate liberation far, far more often than it is used to communicate hate. In fact, baked into the DNA of queer is a refusal to let the forces of hate and oppression have the upper hand or the last word.

Ultimately, if you unilaterally reject the word queer, refuse to use it, warn others to avoid it, you erase me (who am I to you, if you can’t say this word?), you side with those who think everyone who isn’t straight and cisgender should strive to blend in with those who are, and you reject the idea that in order for all people to survive and thrive we need transformation (not just superficial change).

So don’t treat queer as off-limits. Use this word to mean what queers ourselves have used it to mean for thirty years now. Glorious nonconformity and defiant deviance. Resistance to the status quo. Fabulous multiplicity and fierce solidarity. A world where all of us can be free.

Questions? Quarrels? Things to add? Comment below! Want to ask a radical copyeditor something? Contact me! Was this post helpful to you? Consider making a donation!

Note: This post was edited on November 21, 2022, to change the featured graphic. You can see the original, and other graphics about queer, here.

This post was made possible by my Patreon community, who support me in being able to do in-depth research and writing on important topics like this one. It was also made possible by these fantastic sources that I highly recommend checking out if you want to go even deeper into the word queer:

- The Queer Nation Manifesto (“Queers Read This”), passed out at New York Pride in June 1990

- Lisa Duggan’s foundational 1992 article “Making It Perfectly Queer” in Socialist Review

- Robin Brontsema’s fascinating 2004 article “A Queer Revolution: Reconceptualizing the Debate Over Linguistic Reclamation” in Colorado Research in Linguistics

- Jeffrey Weeks’s 2012 article “Queer(y)ing the ‘Modern Homosexual’” in Journal of British Studies

- Jacek Kornak’s 2015 doctoral dissertation Queer as a Political Concept, which painstakingly tracks the evolution of the word queer and the birth of queer theory

I also highly recommend the delightful and accessible book Queer: A Graphic History by Meg-John Barker and Jules Scheele.

Hi Alex, thanks for this article. Very thoughtful and useful and not just because I’m a copy editor and want to know what’s going on out there in editing terms. Thank you for elucidating some things I’d been wondering how to phrase in my personal writing, a great deal of which has to do with queer currents in my life. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Odd really because a trans Trump-lover is, from my perspective, as about as queer a thing (in the original sense) as it’s possible to get. It just goes to show that language evolves and that the slant put on a word will vary from one generation to the next based on their experience. Take ‘woke’ for example which for a while was just bad grammar, then politically positive and is now rapidly becoming a slur. A friend’s post was censored by Facebook recently because she referred to a character in her novel as an ageing dyke, like herself. So it turns out that Facebook is denying her the option of self-identifying that way. A black friend can refer to himself as “this nigga” and it’s funny – but it would feel really uncomfortable for me to use that term.

LikeLike

Beautifully written, as always!

LikeLike

I read each article you send very carefully, and your work has really spoken to me and inspired me, but I just wanted to share that this article in particular was so fascinating and enlightening, not only from the historical perspective, but from a personal perspective as well as I think about myself and even my friends – one phrase you wrote: “Ever since individuals started to form community as same-gender-loving people more than a century ago, there has been a push-pull dynamic between those who want to blend in with the mainstream and those who want to wildly redecorate the whole world” reminded me so much of the first person who put me in drag. Anyways, thank you for always writing what I love to read.

Jackie

LikeLike

I’m so delighted to hear this, Jackie! I’m gratified to know that my blog is useful and inspiring to you, and that this particular post called up such a fabulous queer memory. Thank you for sharing!

LikeLike