Okay, friends. Let’s talk about land acknowledgments.

For those who are unfamiliar, a land acknowledgment is most often understood as a verbal or written recognition of the original Indigenous nations whose lands are being occupied by a person, group, event, school, or other organization.

In recent years, land acknowledgments have become more and more common among people, groups, and organizations with a progressive or social justice-seeking orientation. You can find them written in website footers, displayed on physical plaques and signs, spoken at the start of everything from sports games to plays to academic conferences to work meetings, included in folks’ Zoom names or at the bottom of email signatures, and in hundreds of other places.

It’s a powerful practice, but it can go sideways really easily, a truth that is constantly pointed out by Native folks. So let’s get into it.

Where does the practice come from?

Acknowledging the land and/or the caretakers of the land is a practice that goes back centuries in many Indigenous cultures.

Cantemaza McKay (Bdewákhaŋthuŋwaŋ Dakhóta, Spirit Lake Nation) offered two beautiful examples of traditional land acknowledgment in a 2019 panel discussion hosted by Native Governance Center. “There are land acknowledgments that Dakhóta people give on an everyday basis,” he shared. “In the springtime … we will put tobacco down in the lake to acknowledge the land, acknowledge the beings that are there that are older than us.” He also shared a story of meeting an Ojibwe man who told him, “I was out in your country—I went to the Black Hills. I know that is Dakhóta land, and when I saw the sign that said you’re now in the Black Hills I pulled my car over, and I acknowledged you and your people and I put tobacco down.”

It is impossible to understand this practice without understanding the significance and meaning of the land in Native cultures. Robin Wall Kimmerer (Citizen Potawatomi) writes with breathtaking clarity and power of the reciprocal relationship between human beings and the land. In her book Braiding Sweetgrass she relates:

“In the settler mind, land [is] property, real estate, capital, or natural resources. But to our people, it [is] everything: identity, the connection to our ancestors, the home of our nonhuman kinfolk, our pharmacy, our library, the source of all that sustain[s] us. Our lands [are] where our responsibility to the world [is] enacted, sacred ground.”

Kimmerer describes the lawsuit filed by the Onondaga Nation to regain title to their stolen homelands, in which they name that “the people are one with the land.” In court, members of the Onondaga Nation argued that they did not seek possession of the land but rather the right to participate in the well-being of the land—the freedom to exercise their responsibility to the land. They had a sacred relationship of reciprocity with that particular land.

So it’s no surprise that events, spaces, and groups with Indigenous leadership might engage in acknowledgment of the land and/or its rightful stewards.

I first experienced such acknowledgment when I attended the 2007 U.S. Social Forum in Atlanta. Indigenous people were members of the conference’s leadership, the conference content included an entire track of programming related to Indigenous rights and sovereignty, and the opening of the conference featured representatives of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians welcoming attendees to the homeland of the Cherokee people.

This sort of welcome is common in Australia, where modern “Welcome to Country” rituals, rooted in centuries-old Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander traditions, have been practiced for decades.

The term “land acknowledgment” (also referred to in Canada as “territorial acknowledgment” and in Australia as “acknowledgment of Country”) is currently most often used to refer to the practice of naming the pre-colonization peoples whose land you are on. Mishuana Goeman (Tonawanda Band of Seneca) notes that the practice became common in New Zealand and subsequently Canada as part of an institutional practice. In recent years it has spread quickly in institutional, arts, and activist spaces.

What’s the point?

“Recognition” is probably the most commonly named purpose of land acknowledgment, and recognition can be a very powerful thing, particularly in places like the United States with a history of genocide, dispossession, and erasure of Indigenous Peoples.

In her wonderful blog post “Beyond Territorial Acknowledgments,” Chelsea Vowel (Métis), notes: “When territorial acknowledgments first began, they were fairly powerful statements of presence, somewhat shocking, perhaps even unwelcome in settler spaces. They provoked discomfort and centered Indigenous priority on these lands.”

Vowel discusses a number of purposes of land acknowledgment, including recognition as a form of (or a move toward) reconciliation, honoring traditional Indigenous protocol, and attempts to create more welcoming environments for the Native people present.

I am particularly moved by this explanation of what land acknowledgment can accomplish, from Donald Eubanks (Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe), who moderated the panel discussion mentioned above:

“When done properly, land acknowledgment helps set a tone that begins to illuminate for people the fact that there is a wisdom within this land and its original inhabitants that should be recognized, celebrated, and learned from. When this wisdom is listened to, acknowledged, it is a powerful resource that builds bridges, unites people of all backgrounds, and helps to move us all forward in a good way.”

Unfortunately, although land acknowledgments “have the power to disrupt and discomfit settler colonialism,” in Chelsea Vowel’s words, “what may start out as radical push-back against the denial of Indigenous priority and continued presence may end up repurposed as ‘box-ticking’ inclusion without commitment to any sort of real change.”

How things go sideways

Here’s the thing: it is equally possible for land acknowledgment to help or hurt, to build toward liberation or perpetuate oppression. At its root, the practice of land acknowledgment is about relationship and solidarity: relationship between Indigenous Peoples and the land, solidarity between Native and non-Native people, and a desire to “(re)write, (re)right, and (re)rite,” to quote Cutcha Risling Baldy (Hupa, Yurok, Karuk), all of our relationships—with each other, with the land, and with all of life.

At its best, land acknowledgment is part of a larger practice of relationship and solidarity; it’s a form of aligning one’s words and actions with one’s values, creating new consciousness and new avenues to materially benefit the lives, well-being, and rights of Indigenous people. At its worst, land acknowledgment reinforces Indigenous erasure, dispossession, and oppression.

The trouble is, a lot of people and organizations genuinely believe they are doing a good and right thing with their land acknowledgment, and truly desire to support Native people—but a lot of other people and organizations don’t have any desire to support Native people; they just think land acknowledgment will make them look good in some way. And, unfortunately, the actions of the well-intentioned ally and the poser who only cares about themself or their optics often produce the same (harmful) impacts.

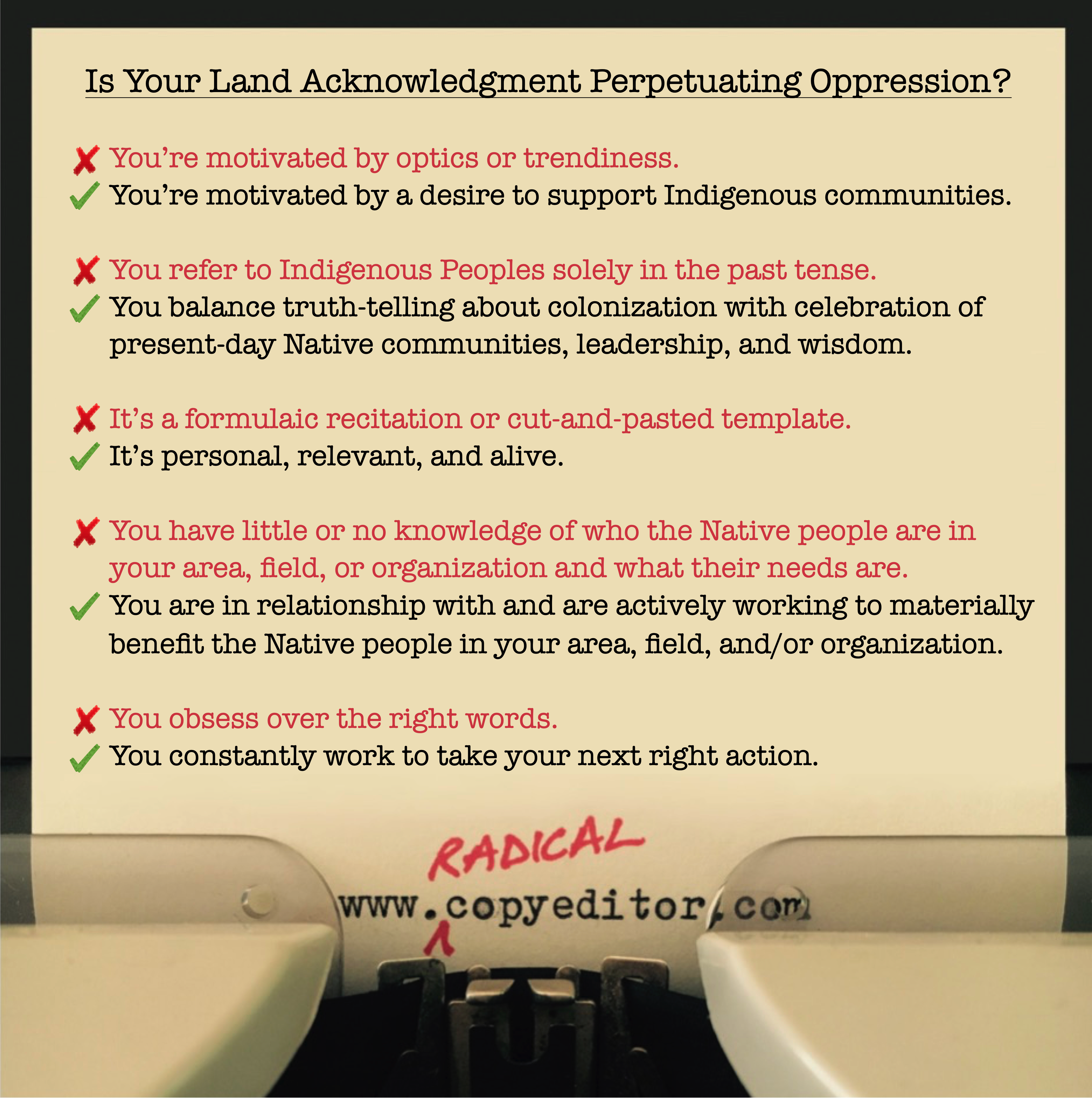

So here are some signs that your land acknowledgment practice may be perpetuating oppression rather than countering it:

- You’re motivated by optics or trendiness

- You refer to Indigenous Peoples solely in the past tense

- It feels like a gloomy memorial to a “lost” culture

- It’s a formulaic recitation that must be “gotten through”

- Facts and/or names are inaccurate, misspelled, or mispronounced

- You don’t know how the land passed from Indigenous to non-Indigenous control

- You have little or no awareness of who the Native people are in your local area, your field, or your organization and what their needs are

- The acknowledgment makes you feel like you’ve done your part

- You or your organization benefits from the continued dispossession of Indigenous Peoples and you neither name this nor seek to remedy it

- Your organization has no relationship with those named in the acknowledgment, or it reached out to a local Native nation for the first and last time to ask them to approve the text of the acknowledgment

- You assume that no Native people are present or will ever actually hear or read the acknowledgment

- The acknowledgment neither includes nor is paired with any call to action

This summer I attended a conference at which conference organizers named whose land they were from as part of their self-introductions and invited attendees to do the same, without fully contextualizing the practice or offering guidance on how to do it well. Several times during the conference’s business sessions, people got up to the mic and blithely said things like, “My name is Mary Smith, my pronouns are she and her, and there are no Native Americans where I live because they were all wiped out. I’m in favor of amendment six because…”

As horrific as this was, land acknowledgments don’t have to go all the way sideways to cause more harm than good. Talking about Indigenous Peoples only in historical terms, using language that implies that they never had any ownership rights over their lands, or playing into caricatures such as the primitive environmentalist (all of which are all too common in land acknowledgments) cause material harm to Native people in large-scale ways.

There’s also the personal impact that half-baked land acknowledgments can have on the Native people who experience them. In the words of my friend Marisol Caballero (Mexica/Rarámuri), “Imagine if several times a week, you had to hear casual reminders of generations of violence on your family with a (oftentimes) side of erasure as if you, yourself, aren’t still breathing air.”

And land acknowledgments can sometimes be counterproductive, notes Wizipan Little Elk (Sicangu Lakota Oyate, Rosebud Sioux Tribe). “The individual who took the symbolic action may feel that they have done their part and are ‘off the hook’ for committing to more difficult and time-consuming work that actually contributes to progress.”

How to ensure that your land acknowledgments “move us all forward in a good way”

As discussed above, land acknowledgment can be a powerful practice that “disrupts and discomfits” oppression. Sometimes simply naming the truth that we are on stolen land is enough to push the needle, depending on the context you find yourself in. So it’s important to understand land acknowledgment as a flexible practice—one that needs to respond to context and evolve in order to keep pushing the needle.

If you suspect your land acknowledgment practice might be half-baked, here are some things to consider:

- Check your motivation: see if you can find your way to being motivated by the desire to support Indigenous communities and inspire others to do the same

- Check your facts, spellings, and pronunciation: don’t just do an online search for “who was here first” and then uncritically copy and paste the first result

- Consider timing and placement: When and where would acknowledgment feel most natural, appropriate, and alive? When and where would it have the most impact?

- Let go of the idea that there is a perfect script or template you should use

- Learn the full history of the land and its people: what is the ecology of the land, how has it been used, who has called it home, how did it come into non-Indigenous control?

- Learn the present reality of the land’s original Indigenous caretakers and the Native people in your local area, your field, and/or your organization: what are they working on, what are their needs, what wisdom do they bring forward?

- Consider how you can balance truth-telling about histories of colonization with celebration of present-day, living Indigenous communities, leadership, and wisdom

- Make it personal: “Acknowledgment is an active thing. You need to be situated in that acknowledgment or it’s lip service,” says Falen Johnson (Mohawk/Tuscarora, Bear Clan)

- Most importantly, pair acknowledgment with action

Native Governance Center has a wonderful guide to land acknowledgment, which includes many of the practices above. They advise asking yourself, “How am I leaving Indigenous people in a stronger, more empowered place because of this land acknowledgment?”

If your answer is, “I’m not,” it’s time to do it differently. “A land acknowledgment should be an obligation,” says Hayden King (Anishinaabe, Beausoleil First Nation). “Instead of spending time on a land acknowledgment statement, we recommend creating an action plan highlighting the concrete steps you plan to take to support Indigenous communities,” urges Native Governance Center in their even better guide beyond land acknowledgment.

Here are some actions you and/or your group, school, church, workplace, or other organization/institution can take to keep your land acknowledgment from being empty words:

- Donate money. Wizipan Little Elk challenges everyone who hears a land acknowledgment to donate at least one dollar to a Native-led organization, noting that of every $100 of philanthropic giving in the United States, Indigenous causes receive only 23 cents.

- Stop harm. Some of the worst land acknowledgments are those given by entities that are actively harming Indigenous communities, such as oil/gas pipeline companies and sports teams with racist names/mascots. But there are many more subtle ways that individuals and organizations cause harm. Check out Native Governance Center’s self-assessment on this topic. Work to identify ways your organization may be causing harm to Indigenous communities and stop or mitigate those harms.

- Remove barriers. Along the same lines, consider what barriers exist for Native people in your community, workplace, school, organization, or field. Is it easy for Native folks to access, contribute to, and feel a sense of belonging in the spaces you move through? How can you leverage your own resources and relationships to create more access, equity, and agency?

- Show up. Actively support Indigenous communities and Indigenous-led groups and movements in your local area and/or your field. Attend and support local events, public festivals, and campaigns. Amplify the voices of Native leaders.

- Build relationships. Has your workplace, school, church, organization, or institution reached out to local Native nations or Indigenous-led groups? If not, consider how to respectfully get in touch and humbly ask if there’s anything you can do to be good neighbors—then do what they ask. Work to maintain and strengthen reciprocal relationships in a long-term way.

- Hire Native people. Compensate Native folks for their time and labor, hire them as consultants and speakers, and seek out Indigenous talent. It bears noting that the unemployment rate for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States is about twice as high as the rate within the general population.

- Challenge settler-colonial narratives. Most people in the United States have absorbed constructed mythologies about Indigenous Peoples. How can you challenge those stories for yourself and others—perhaps starting with Thanksgiving and Indigenous Peoples Day and then finding ever-deeper ways to decolonize your worldview?

- Practice reparations. Dig deep into the history of your family, neighborhood, school, church, institution or organization, field of work. Where did its wealth come from? How did it acquire land? Was it involved in the destruction of sacred sites, the theft of artifacts and ancestors, the breaking of treaties, the assault on Indigenous culture, livelihoods, and lives? If so, what would a move toward reparations look like? Returning artifacts and ancestors, creating Native-dedicated scholarships or fellowships, divesting from gas pipelines and reinvesting the money into Indigenous initiatives?

- Engage with the land back movement. Land back is a growing movement to return Indigenous land to Indigenous control. A related creative practice is to pay voluntary land taxes to the nations whose land you are on. Learn more about land back and land taxes and how you can get involved via Resource Generation’s Land Reparations & Indigenous Solidarity Toolkit.

But what are the “right words”??

I’m a copyeditor, after all, so maybe you were hoping I would tell you what words to use in a land acknowledgment (although if you’ve spent any time on my blog you probably know that’s not how I roll). I’d like to direct you to this reflection from Native Governance Center:

“Our organization has received hundreds of inquiries from folks wanting help with their land acknowledgment statements. Almost all of these inquiries have focused on land acknowledgment verbiage, rather than the all-important action steps for supporting Indigenous communities. Every moment spent agonizing over land acknowledgment wording is time that could be used to actually support Indigenous people.”

It’s a maxim of mine to care more about people than about words. So if you find yourself obsessing over the “right words,” I recommend taking a step back and returning to the larger question of how to practice care for the people at the heart of this topic.

If you don’t yet have a land acknowledgment practice, maybe start with action first, and then let your practice of acknowledgment flow from your actions and the new relationships and understandings that result from that action.

If you or an entity you’re part of already have a land acknowledgment practice, check in about how you can materially support Indigenous people. Keep evolving your acknowledgment practice and keep pairing it with new actions across lines of nation, race, and place for the survival, sovereignty, and well-being of Indigenous Peoples.

Check out these great sources for more insights and recommendations:

- “A Guide to Indigenous Land Acknowledgment” from Native Governance Center

- “Beyond Land Acknowledgment: A Guide” from Native Governance Center

- Land acknowledgment panel discussion hosted by Native Governance Center

- “Rethinking Land Acknowledgments” by Michael Lambert, Elisa Sobo, and Valeria Lambert

- “Every Time I Hear a Land Acknowledgment…” by Wizipan Little Elk

- “Beyond Territorial Acknowledgments” by Chelsea Vowel

This post was informed by the wisdom in the resources above, by the incredible blessing of being able to do faith-based environmental justice work with the Lummi Nation a number of years ago, and by the relationships with Native friends that have so enriched my life and my worldview. I offer this piece in love to them and in memory of my chosen sibling Lynn Young (Lakota), who was taken by covid three years ago today.

If this post was helpful to you, please consider showing your appreciation by making a donation to LANDBACK, Native Governance Center, the Indigenous Environmental Network, or an Indigenous nation or Native-led organization in your area.