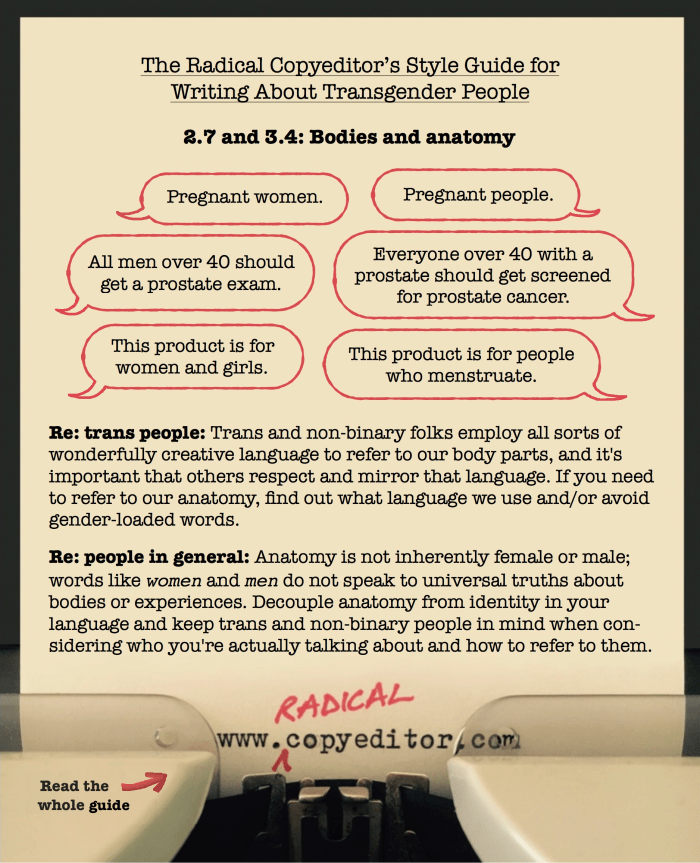

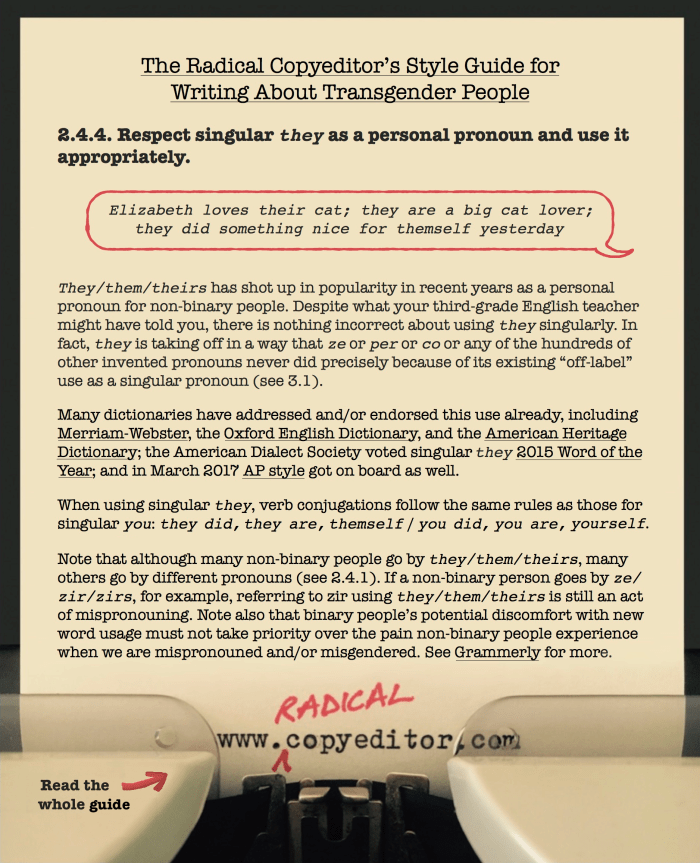

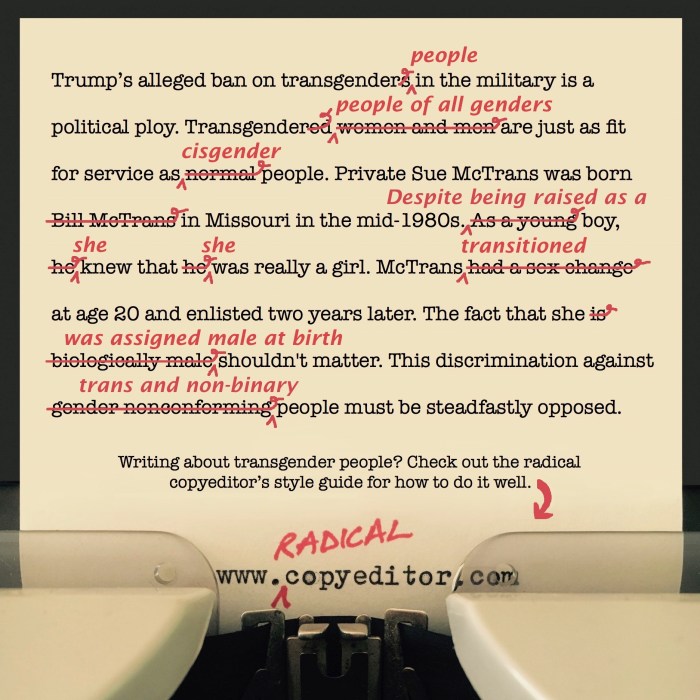

Today I made a third major update to The Radical Copyeditor’s Style Guide for Writing About Transgender People to add four sections on how to avoid writing or talking about trans people in ways that are invalidating or otherwise harmful. (Remember that context is everything, and that all trans people have a right to describe themselves in whatever language feels best to them.)

I also updated section 1.4 and the note that follows it to reflect better language that has emerged for instances when you want to be clear that when you say trans you aren’t referring only to trans women and men but also non-binary people, as well as the recent trend in trans communities to perceive trans and transgender as having separate meanings.

Continue reading “Update to Transgender Style Guide: Avoiding Invalidating Language Traps”