As a young person in the ’90s, one of the first and foundational experiences of radical copyediting I had was when I encountered folks who advocated for calling abortion opponents “anti-choice” rather than using their own term for themselves—“pro-life.” It was immediately apparent to me how powerful words were in shaping perception, and how vital it was to not lend validity to the mythology that the anti-abortion lobby is primarily concerned with “life.”

Back then, I couldn’t imagine a world without Roe v. Wade, but I also couldn’t imagine a world in which trans and nonbinary people like me were seen as real and valid and worthy of visibility in language. Today, those who understand the power of words are tasked with a new challenge: how to talk about the wreckage of Roe and who is being most impacted without erasing anyone.

The landscape of gender, bodies, rights, justice, and language is super complex and nuanced, so our approaches to it have to be complex and nuanced too. Here are seven practices that can help.

1. Talk about women. Just don’t erase everyone else.

X “Only women suffer any consequences of an unwanted pregnancy.”

X “Stop centering women in discussions around abortion!”

✓ The overturning of Roe v. Wade represented a culmination of decades of strategic organizing against women’s rights and bodily autonomy.

I’m a 38-year-old nonbinary person. When I was coming into an understanding of my gender in the mid-’00s, I never thought I’d ever see a day when people like me were acknowledged as real. I’ve experienced a lot of invisibility, and I know the toll it takes.

That said, it is absolutely appropriate—and essential—to talk about cis women in discussions of abortion, because efforts to restrict or criminalize abortion have always explicitly targeted cis women. As the group that has been overtly deemed underserving of rights or decision-making power with respect to this issue, cis women need to have a central voice, particularly those who have been most disempowered and most negatively impacted by attacks on abortion access, such as cis women with low or no income, cis women of color, disabled cis women, and undocumented cis women.

Trans men and many nonbinary and intersex people are also impacted, but our main struggle in this area comes from not being seen as real. It makes sense to talk about abortion in the context of women’s rights (particularly the longstanding lack of those rights)—just make sure that you don’t render trans, nonbinary, and intersex people invisible in the process.

The key is to use a lens that encompasses both gender diversity and anti-misogyny. It’s essential to be mindful of people who are trans, nonbinary, and/or intersex while never losing our grasp on how patriarchy, sexism, and misogyny are explicitly designed to demean, diminish, and disempower women.

2. Avoid assumptions about who does or doesn’t need abortion access.

X “If men could get pregnant, abortions would be available at Jiffy Lube.”

X “People like you don’t have to worry about unplanned pregnancies.”

✓ It’s unconscionable for people who will never need an abortion to control access to them.

(Some) men can get pregnant. A significant portion of trans men have planned or unplanned pregnancies and/or pursue abortions. Some experience pregnancy prior to coming out as trans; others do afterward. Trans men are men; therefore, some men need abortions. When “men” is used synonymously with “cis men,” it erases trans people—just as when “women” is used synonymously with “cis women” it erases trans people. It can also add to the myriad barriers that trans people experience when we are in need of reproductive health services, which is all too often a site of erasure, mistreatment, or worse.

Think people in same-sex relationships don’t have unplanned pregnancies? Compared with straight teen women, lesbian teen women are approximately twice as likely to experience an unplanned pregnancy, and bisexual teen women are approximately five times as likely.

It makes sense to be angry and feel like many of the people with the most power to control and criminalize abortions shouldn’t even have a say, much less a deciding voice. But place your anger and your words where they belong, rather than making sweeping statements or assumptions.

3. Reducing people to body parts is not the best way to be inclusive.

X “People with uteruses” “Uterus-havers” “Women and other people with uteruses”

✓ “People who can get pregnant” “People who need abortions”

If you are in a healthcare setting and you are literally talking about body parts and the care that those parts need, such as HPV screenings, risk of endometriosis, and so on, then it’s appropriate to talk about uteruses and people who have them. But if you’re talking about abortion rights and who needs them, it’s kind of crummy to talk about folks as if their defining characteristic is their possession of a uterus and/or their capacity to give birth—that’s actually more in keeping with what the anti-abortion lobby tends to do.

A lot of people have taken to using the phrase “people with uteruses” in a well-intentioned attempt to be trans-inclusive. But not only does this focus feel subtly dehumanizing and medically objectifying, it also ignores the fact that although lots of people of many genders feel a positive connection to their uterus, many folks really don’t. A lot of trans men in particular would prefer that strangers not think about (and define them based on) their reproductive anatomy.

Also, not all people who have a uterus can get pregnant, so using “people with uteruses” as shorthand for “people who can get pregnant,” erases many intersex folks, post-menopausal folks, people who have had various surgeries, and more. If you’re talking about pregnancy and/or abortion, just talk about pregnancy and/or abortion, rather than body parts.

4. Consider when gender is relevant and when it’s not.

In general, gender is not relevant if you’re just talking about the biological reality of pregnancy. Gender is relevant if you’re talking about patriarchy, misogyny, cissexism, and/or the erasure of trans, nonbinary, and intersex people. Let’s break that down.

When gender is irrelevant: Although most people who get pregnant are cis women, others do too: cis girls, trans boys and men, and nonbinary and intersex people with the equipment for growing babies. So when you’re talking about pregnancy, plain and simple, there’s no need to specify the gender of the people involved—just like there’s no need to specify the gender of people with heart disease or baldness. What’s relevant is the condition, not the gender of the people in question.

⇒ Check it out: the phrase “pregnant women” is actually an example of how everyday language treats men as the default. Words like “actors,” “comedians,” and “authors” can include women (despite the existence of “actress,” “comedienne,” and “authoress”), but words like “stewardesses” can’t include men (gender neutrality required a new term, “flight attendant”). Patriarchy dictates that “person” means “man” by default, so “pregnant person” is an affront to male supremacy.

When a medical form asks if I have a history of smoking, I say no, and move on. But asking a cis man if he might be pregnant is considered so offensive that including this question requires a separate “women-only” section or form, to ensure that men don’t encounter it.

When gender is relevant: If you’re talking about gender-based oppression, gender is entirely relevant. In discussions of abortion and whether people have the right to bodily autonomy and control over their own health decisions, we’re never just talking about the biological reality of pregnancy—we’re talking about rights. That means we need to talk about whose rights are being trampled. And it’s not “pregnant people,” because folks aren’t oppressed due to having the capacity for pregnancy—they are oppressed because they aren’t cis men, in a social order designed to systematically empower men, disempower women, and erase anyone who doesn’t fit neatly into that binary. So it’s vital to talk about gender in such contexts.

5. Practice care in how you engage with others about their words.

X “The term ‘birthing parents’ erases women!”

X “Talking about the ‘war on women’ is transphobic!”

✓ Hey, that word choice was tough for me because it made me feel invisible.

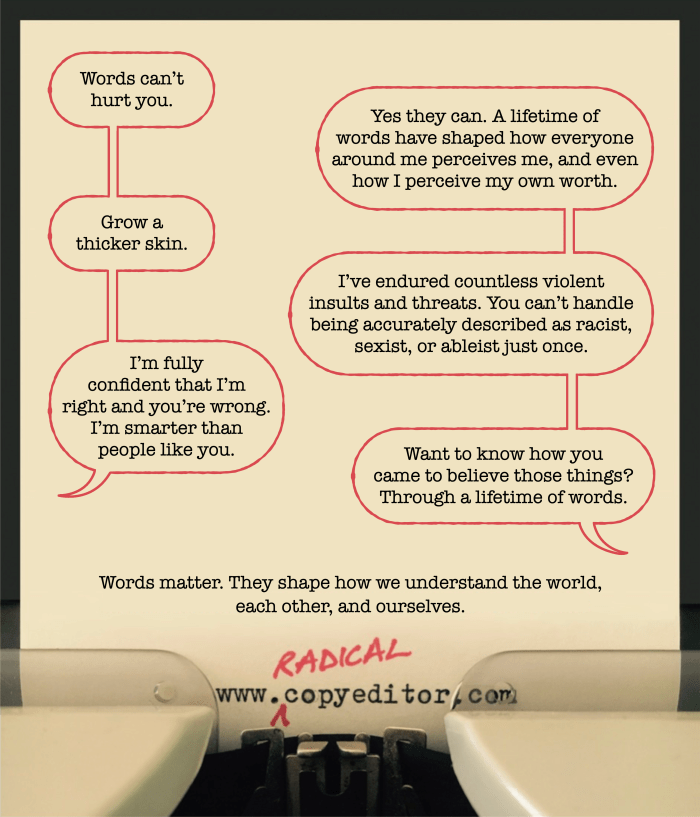

We all know the person who jumps on others—usually on social media—for not using the “right words.” Please don’t be that person. Radical copyediting is not language policing. Words really matter, but it also really matters how we engage each other.

If you are personally affected by this topic and you encounter someone using words that feel hurtful or erasing to you, consider whether and how to best engage with them. It’s important to not give people a pass on language that perpetuates oppression, but it’s also important to not shame people for not having the best words—particularly if they have also suffered because of the anti-abortion lobby. If you are not personally affected by this topic and someone asks you to reconsider your word choices, listen deeply, do your homework, and keep in mind how painful this topic is for so many folks.

It also helps to keep in mind that one of the ways oppression works is to keep folks with a common enemy (e.g., gender-based oppression) divided and fighting each other instead of working together for collective liberation.

6. Consider the best ways to create more visibility for people who are trans, nonbinary, and/or intersex.

Let’s be real: this stuff is tricky. In a better world, we wouldn’t have to remind people that not everyone is cis, and we also wouldn’t have to remind people that women are full human beings worthy of self-determination. Such a world is worth working toward, but we don’t live there yet.

Right now, for most people the word “women” means cis women and “pregnancy” is synonymous with a gender binary understanding of femaleness. (To the rest of us, “women” means all women—cis women, trans women, intersex women, and woman-adjacent nonbinary folks who are feeling woman-y today—and “pregnancy” doesn’t have to have a gender.)

This means that gender-neutral language like “people who can get pregnant” doesn’t actually visibilize gender diversity to many people, because the majority of folks think such phrases are synonymous with “women.” And some are capitalizing on this unclarity of meaning in transphobic ways, such as claiming that trans people are trying to erase (white, cis, affluent) women or that anyone who uses such language is being absurdly politically correct (which is never a compliment). (See, for example, Missouri Senator Josh Hawley’s reaction to law professor Khiara Bridges’s use of the phrase “people with a capacity for pregnancy” in a July 2022 Senate hearing about the reversal of Roe v. Wade.)

So it’s often not enough to “neutralize” language, because doing so won’t challenge many people to think beyond the binary. If you say “birthing parents” their brains will translate it as “mothers” and move on. In the interest of clear communication, we sometimes need to explicitly name who we are talking about, as in “we are fighting for everyone who can get pregnant, including cis women, trans men, and many non-binary and intersex people” or “this bill is an issue for the millions of women and trans people in our state who need access to abortions.”

The key here is to know your audience and use language that will help expand, rather than contract, understanding and awareness. There is no one-size-fits-all phrasing that will work in every scenario, but there is always a way to reduce harm and increase awareness of who is hurt by lack of access to affordable and safe abortions.

7. Complicate the narrative.

As nuanced and complex as everything above might already seem, there are always more layers to explore, unpack, and make plain when fully engaging with this topic.

For one thing, language is also cultural, so although many of the examples of inclusive language I’ve used in this piece use phrases like “trans men and many nonbinary and intersex people,” that doesn’t mean those are the best words in all contexts. I am a white, college-educated person in the United States who only speaks English, and the words I use reflect that cultural location. Other contexts call for different language (which I talk about more over here).

It’s also important to not think about or talk about any group of people—including cis women—as a monolith, because that often makes white, nondisabled, affluent people the norm. It’s vital to be clear about not only who has the least access to reproductive health care in general and abortions in particular, but also how anti-abortion rhetoric has long been explicitly constructed in racist and classist ways, and the need to counter these harmful stories.

Finally, one of the deepest layers when it comes to this topic is the fact that the anti-abortion cause and the much newer anti-trans cause are parallel political tactics in the United States. Both were intentionally designed as banner causes under which political conservatism could unify and strengthen its base. Both were fabricated, with scripts (from the same playbook) handed out to key players such as Republican legislators and Evangelical Christian leaders, and both make false claims (caring about “life,” “saving girls,” or “protecting children”) that rely on and further gender-based oppression. It is well worth knowing and sharing this history.

Remember: nuance and complexity are worth it. In times of crisis, it’s understandable to want to find the simplest, easiest words that can communicate that crisis, but taking linguistic shortcuts can cause a lot of harm. The more people we bring along, the more likely we are to achieve our goals, and using words intentionally and consciously is part of how we can build coalitions.

Words are never just words. At the end of the day, the language we use is a reflection of who we are thinking about, who we are in relationship with, and who we are ultimately fighting for. Personally, I’m fighting for all of us to get free. I hope you will too.

This piece was a collaboration with the brilliant Han Koehle and Teo Drake, who contributed vital insights and helped shape the piece. I’m particularly indebted to Han for the impetus to create a post on this topic and the generative initial conversation that started it. If you found this piece helpful, please consider showing your appreciation by making a donation to Han or better yet joining their Patreon.

More posts you might like:

Thank you for this!

Because I have absolutely seen trans people and their Allie’s advocate to stop centering women in these discussions.

LikeLike

Best thing I’ve read in a long time. Thank you. Kim

>

LikeLike

Great post! Thank you!

Melissa

Get Outlook for Androidhttps://aka.ms/AAb9ysg ________________________________

LikeLike