Last month I was honored to deliver the keynote address at the annual conference of the Publishing Professionals Network, a San Francisco Bay–area nonprofit that supports people working in the book publishing field. The theme of the conference was “Publishing in a Diverse World.” It was a wonderful gathering of folks invested in using books as a tool for positive change. Here’s what I shared with them, slightly edited for publication purposes.

There are a few things that are important for you to know about me. The first is that I am a major word nerd. The second is that I’m a preacher. And the third is that I’m an organizer. Now, where I come from, it’s important to define your terms. Where I come from we recognize that we can’t just throw words out there and expect our meaning to be clear. And I want to be clear.

So when I say that I’m a word nerd, I mean that I love words. I mean that I follow in a lineage of critical thinkers and language shapers, particularly Black women like Toni Morrison, Octavia Butler, Audre Lorde, Barbara Smith, and so many others who have changed the world through the power of words. I’m the kind of word nerd who delights in the art form that is language and wants to help others fall in love with words too.

And when I say that I’m a preacher, I mean that I can’t help but share with others the call I feel to live in ways that are aligned with life. I mean that I follow in a lineage of liberationist theologians like Pauli Murray, Gustavo Gutiérrez, Howard Thurman, and Ibrahim Farajajé—people who practiced faith as a revolutionary force. I’m the kind of preacher who wants to help you remember what matters to you and why.

And when I say I’m an organizer, I mean that I’m working toward liberation. Not from clutter—I’m not that kind of organizer. I’m an activist who’s working to help us all get free from all forms of violence. I mean that I follow in a lineage of fellow white people dedicated to being traitors to racism, fellow temporarily nondisabled people dedicated to eradicating ableism, fellow middle-class folks dedicated to building a world beyond classism, caste-ism, and capitalism. I’m the kind of organizer who wakes up in the morning excited to help other people unlearn the things that get in the way of all of us surviving and thriving.

The thing about language is, simply telling you that I’m a word nerd, a preacher, and an organizer doesn’t really communicate any real truth of who I am and what I do in the world, because there are so many different associations and histories and flavors attached to those terms. And I need you to know what flavor of word nerd, preacher, and organizer I am because I am on the side of love, and joy, and life, but I have met word nerds who proudly self-identify as grammar nazis, I have met preachers who condemn people to hellfire and damnation, I have met organizers who cut others down and cast them out of community for being imperfect. I need to be clear that I am not the kind of person who uses words, faith, or activism to arbitrate right from wrong.

In short, I need you to understand that I am about care, not correctness. I don’t believe being correct is achievable or a worthy goal to begin with. And that is often seen as a surprising position for an editor to take—particularly a copyeditor! But I’m here to tell you why I believe that publishing in a diverse world requires all of us to orient ourselves toward care, not correctness.

So, leaving religion and activism for a bit, let’s talk about words, because that is the craft that all of us here today share—all of us, one way or another, are in the business of words. And if you’re like me, if you’re like the vast majority of people raised in the United States or any number of other countries, you have been taught that there is a correct way to use words.

Most of us have absorbed the idea that “correct” language is proper, polite, good, neutral, and follows societal rules for how to speak and write well, and “incorrect” language is improper, impolite, bad, biased, or deviates from those rules, whether we’re talking about spelling, subject-verb agreement, or what term to use to describe a particular group of people.

And many people think that being an editor means being all about rules—constantly seeking out incorrect language and making it fall in line through the cunning use of red ink. But being a good editor means questioning the rules, and figuring out which ones to apply in which contexts, right? Whether you work in development or production or marketing, whether you’re in a news room or even if you are on the writing side of the equation, working with words means attending to what standards to use in response to the context. Are you working with print media, web media, or social media? Are you using Chicago Style, APA, or AP? Are you working on a cookbook or a research study or a poetry zine? Is it written in U.S. English, British English, or Australian English? We have to attend to context in order to figure out which standards to apply.

I like to think I’m a good editor. I’m also a radical editor. To me, while being a good editor means knowing the rules, and knowing how they change from context to context, being a radical editor means knowing where rules come from, who they serve, and who is negatively affected by them—and then making mindful decisions about which ones I enforce.

Angela Davis reminds us that despite the way the word “radical” has been twisted, at base it simply means “grasping things at the root.” Radical politics understand that social problems must be grasped at the roots. Radical editing means getting to the root of where rules come from and the impact they have, and then making conscious choices from that place.

The thing is, English is a bit of a mess. So we need rules to help us use it effectively. In the words of author Daniel José Older, “The function of language is to communicate things clearly. The function of grammar and rules around language are to facilitate that communication.” Given how many people speak this quirky language of ours in so many places and so many contexts, without language standards a lot of us wouldn’t be able to understand each other across those lines of difference. Also, I’ll be honest: as a copyeditor, I love rules! I love punctuation. I love clarity of syntax. I love a beautifully consistent, perfectly ordered reference list.

But not all language rules are created equal. There are many rules that are rooted in helping people understand each other, in helping meanings be clearly communicated, but there are other rules that are rooted in uplifting the “best” ways of using language, where what’s best aligns with power—the way people with the most societal status use language. And there are still other rules that are rooted in nothing more than the whims and fancies of people who had the resources and the clout to get published and influence others.

Some people talk about the tensions between all of these disparate rationales in terms of prescriptivism and descriptivism, where prescriptivists dictate how people should use language and descriptivists simply describe how people are using language. I find this framework informative but also limiting. Far more useful, to me, is the question of why rules exist and what impact they have, regardless of whether they are prescribed or described. As a radical editor, I want to follow standards that help people understand each other across lines of difference. I’m less keen on empty rules that serve no useful function, and even less keen on rules that only serve to prop up elitism.

Let’s talk about a few examples.

One of the most influential early textbooks on how to use English “correctly” was published in 1762 by Robert Lowth, a scholar and a bishop in the Church of England. In her book The Bishop’s Grammar, scholar Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade shows that Robert Lowth initially wrote his book as a tool to help his son access a higher social class. He set out to document the way his social superiors—the aristocracy—used language, and his book was wildly successful because a growing upwardly mobile middle class was eager to learn the “norm of linguistic correctness” (or “polite usage”) that accompanied the status they aspired to.

One of the many rules that can be traced to Robert Lowth’s book is the rule against double negatives. Lowth claimed that two negatives cancel each other and create a positive statement, an argument that persists today, 250 years later. The problem is, it’s just not true. When Mick Jagger sang “I can’t get no satisfaction,” it clearly communicated a stronger negative, not a positive. When people say “you’re not wrong,” it communicates something slightly more nuanced than “you’re right.”

The double negative is useful, has been widely used forever, and isn’t always equivalent to an affirmative. So the idea that double negatives are “illogical” is a false argument. The real reason there’s a rule about double negatives is that they are associated with people who are lower class, an association that is still very much alive and well today. In the U.S., double negatives are particularly prevalent in Black speech, Southern speech, and rural speech. In Black English (also called African American Vernacular English) the phrasing, “He ain’t never without a job; can’t nobody say he don’t work” is perfectly grammatically correct. Despite the long history of Black English being judged and demeaned as “broken” English or just plain wrong, it’s a full-fledged dialect with its own unique syntax and grammar rules. It’s not incorrect; it’s simply different. At the end of the day, the fact that double negatives aren’t used in “professional” writing isn’t about what’s “correct,” it’s about oppressive stereotypes about certain people being unintelligent and lesser-than.

How about the rules that you shouldn’t split infinitives or end sentences with prepositions? I’ll be honest, when I first encountered these rules as a baby editor I was flummoxed. They felt so bizarre and stilted and I couldn’t make sense of what they accomplished. So I was fascinated to learn that, according to Amy Einsohn, author of The Copyeditor’s Handbook, many rules, including these two, originated in “the desire of British elites, beginning in the late sixteenth century, to confer grandeur on the English language and the burgeoning English empire through the imitation of classical Latin and the august Roman Empire.” The “perfection” of Latin was believed to be connected to the success of the Roman Empire; many people thus thought England’s own political expansion required making English as “perfect” as Latin. And the best way to do that, they concluded, was for English to act more like Latin.

So it turns out that the rules against ending sentences with prepositions (as in “What are you talking about?”) or splitting infinitives (as in “to boldly go”) are both based on the fact that in Latin, these things are impossible. You literally can’t split infinitives or put prepositions at the end of phrases in Latin. The idea of trying to make English grammar conform to Latin grammar is utter nonsense, because English and Latin have completely different grammatical structures. But that didn’t stop a lot of people from trying.

So not only are these rules nonsensical, they’re rooted in empire—in the desire to make English a language worthy of the most powerful empire of all time, an empire that could conquer and colonize countries all over the globe. And prohibiting terminal prepositions and split infinitives truly serves no purpose other than separating people who have been formally trained in Standard English from people who haven’t. Which, to me, is a pretty crappy and elitist reason to uphold a rule.

Finally, let’s talk about today’s cause célèbre—singular they. Maybe you’re fully on the “they” train and love singular they. Maybe you have a nails-on-chalkboard experience every time you encounter a singular use of “they.” Maybe both are true at once, or you’re on the fence—no shame!

Let’s talk facts. The reason people have to be so forcibly taught not to use singular they is because it is, in fact, English’s easiest and oldest generic third-person singular pronoun, and everyone uses it singularly. Shakespeare did it. Austen did it. You do it. “Who left their umbrella here? I hope they come back for it.” “Who’s on the phone? Tell them I’ll call them back.” Right? Lexicographers have traced the consistent use of singular they all the way back to 1375. It’s literally older than Modern English and our present-day alphabet.

So where did the rule that we shouldn’t use “they” singularly come from? In a nutshell, patriarchy—with some more Latin mimicry thrown in for good measure. According to Dennis Baron, one of the foremost scholars on singular they, the idea that “he” should be the generic third-person pronoun has its roots in the “worthiness doctrine,” which was introduced in Latin grammar textbooks in the sixteenth century. This influential rule stated that “the masculine gender is more worthy than the feminine, and the feminine more worthy than the neuter” and dictated which gendered adjective form to use when describing a group of differently gendered nouns. No one tried to apply this rule to English for another two hundred years, because English, unlike Latin, doesn’t have grammatical gender. But in the mid-1700s grammarians decided that “he” should be used instead of “they” to refer to singular nouns of unspecified gender, like “everyone” and “somebody.”

The general public wasn’t too keen on this idea and kept using “they,” but the elite club of (mostly male) British grammarians were stuck on it, and increasingly argued against singular they, to the degree that in 1850 an Act of Parliament was passed that legally asserted that “he” stood for “she.”

Fast forward another fifty years and women started arguing, throughout first-wave and second-wave feminism, that that was crap, so the constructions “he or she” and “his or her” and “he/she” came into vogue. Which was okay, but people still used “they” because it was so much easier. So what we are seeing today is a reestablishment of English’s true and consistent use of “they”—both plural and singular—and a rejection of a rule that never should have been a thing and has never been followed by the vast majority of English speakers.

This particular language rule is really personal to me, because I’m nonbinary. I actually don’t use “they” as my own personal pronoun; in various contexts I use “ze” and “per,” “he” and “him,” or no pronouns at all. But that’s beside the point. According to the rules we’ve been taught, I don’t exist. There’s no room for the truth of my gender in what we’ve been told is the “correct” way to be, the correct way to talk and write, the correct way to understand the world and interact with one another.

And it is a heavy load, particularly right now, in a political moment of exponentially escalating anti-trans rhetoric and legislation, when people say that a language rule is more important to them than my existence. As far-right pundits literally seek to annihilate transness and trans people, the very least we can do is create a little more linguistic room for the existence of trans people.

You see, some of the rules of English—some of the rules those of us who deal in words are often expected to uphold—have real impacts.

So we have to be guided by care, not correctness. If our goal is to do good in the world, we have to be willing to ditch rules if they are causing harm. We have to attend to context, and discern which standards to follow in which contexts—not based on being correct for the sake of being correct, but based first in the principle of do no harm and second in the practice of facilitating communication across lines of difference.

There’s another way that word craft is often boiled down to being correct that I want to talk about today, and that’s political correctness.

There are a lot of people, across the political spectrum, who believe that caring about words and striving to use them in ways that are anti-oppressive is about political correctness. Terms like “conscious language,” “inclusive language,” “equity language,” “bias-free language,” “sensitive language”—all of these terms basically describe the same practice, and it’s a practice of attending to the power of language to wound or heal, oppress or liberate.

If we buy into the framework of political correctness, then we are basically buying the idea that there is a perfect way to use words that will avoid offense.

Merriam-Webster, my personal favorite dictionary, bears this out. If you look up “politically correct,” the definition listed is “conforming to a belief that language and practices which could offend political sensibilities (as in matters of sex or race) should be eliminated.”

So is this a worthy goal? Is the goal of attending to the power of language ultimately about censoring words in order to avoid offense? My answer is a resounding no. Just like with language rules, I believe we need to practice care, not correctness, when it comes to striving to use language in ways that are responsive to racism, classism, ableism, sexism, and other oppressions.

How would you feel about me taking you on one more nerdy deep dive into the origins of “politically correct”? Because it’s fascinating. (Remember, I’m a word nerd!)

Okay check this out. The term “politically correct” dates back, at least in the United States, to the 1940s, when Socialists and Communists clashed over Stalin’s alliance with Hitler. The Communist Party doctrine was called the “correct” party line. Jewish educator, author, and activist Herbert Kohl explains that “the term ‘politically correct’ was used disparagingly to refer to someone whose loyalty to the [Communist party] line overrode compassion and led to bad politics.” People who were “politically correct” were people who brushed off racism and genocide because the party line was more important than actual people’s lives. Correctness trumped care.

Flash forward fifty years, and right-wing intellectuals began using the term “politically correct” to disparage people who were seeking to combat racism, sexism, and homophobia in higher education in the early 1990s. Herbert Kohl noted that neoconservatives intentionally appropriated the term politically correct to insinuate that egalitarian democratic ideals are actually authoritarian because they oppose the right to be racist, sexist, and homophobic. The term politically correct was weaponized as a defense against criticism and as a way to divert attention around bias within education to issues of freedom of speech, ignoring that the right to question bias in the education system is itself a free speech issue.

So this phrase, “political correctness,” communicates that what’s going on is censorship and restricting free speech, simply to conform to a political “party line” that tip-toes around people who are intolerant of harmless, rough words. And it’s not just neoconservatives. Neoliberals also love to trumpet the dangers of political correctness “gone too far” and how the left is shooting itself in the foot by striving for some sort of ridiculous “linguistic purity” and ignoring the real problems of the real world, right?

Language isn’t correct or incorrect, it’s contextual. When I strive to use language in ways that are inclusive of the full diversity of human experience, it’s not about being correct or avoiding offense. It’s not about censorship or restricting language. It’s about expanding language, creating more room for more people and perspectives. It’s about empowerment, and agency, and collective care. It’s about liberation—working toward a world in which all of us are free from all forms of violence.

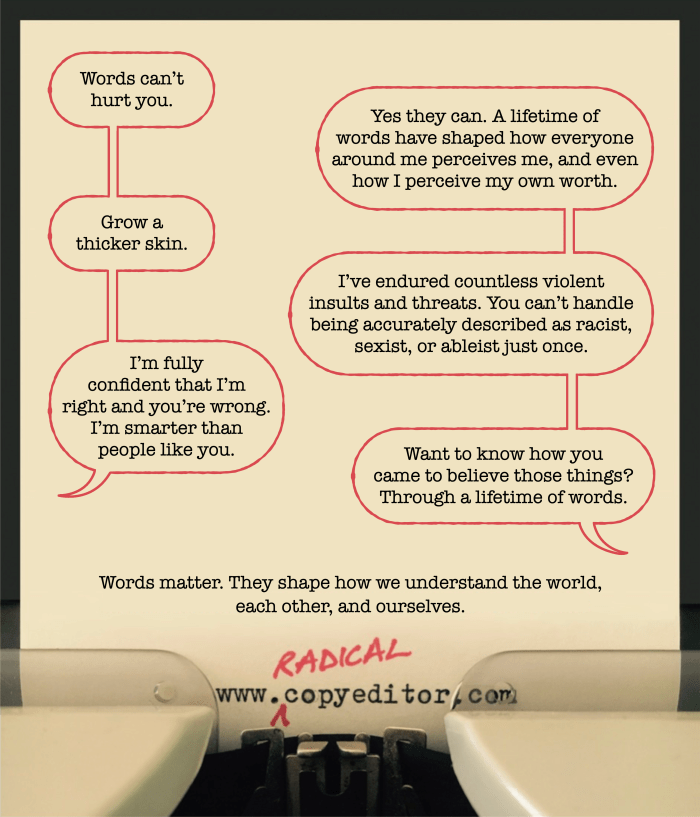

The idea that avoiding “offending” people is the primary goal and the worst thing that language is capable of doing is inherently minimizing and categorically untrue. It automatically calls up the idea that being offended is a result of being either overcritical or oversensitive, and it scoffs at the idea that sticks and stones can break my bones but words can crush my soul.

Not only does focusing on “offense” not allow for the possibility that words can contribute to actual violence and bodily harm, not just hurt feelings, it also shifts the focus when it comes to the speaker or writer as well. If I strive to be “correct” and “avoid offense,” I’m ultimately focused on myself. I’m looking out for my interests; I’m working to maintain my self-concept as a good person or striving to avoid bad press. If I use what I think are the “correct” words and someone gets offended, that must be their fault. But if I strive to be caring and avoid harm, that’s really different. Avoiding harm means I attend to the impact of my words on others and take responsibility for that impact.

Avoiding offense and being “correct” is not the point of anti-oppressive, conscious, inclusive language. The real issue is that language can perpetuate violence, not that it can “offend” people.

This whole mythology and sleight of hand around “correct” language also keeps us focused on individual, one-time uses of language, rather than the accumulated effects of language on population and societal levels.

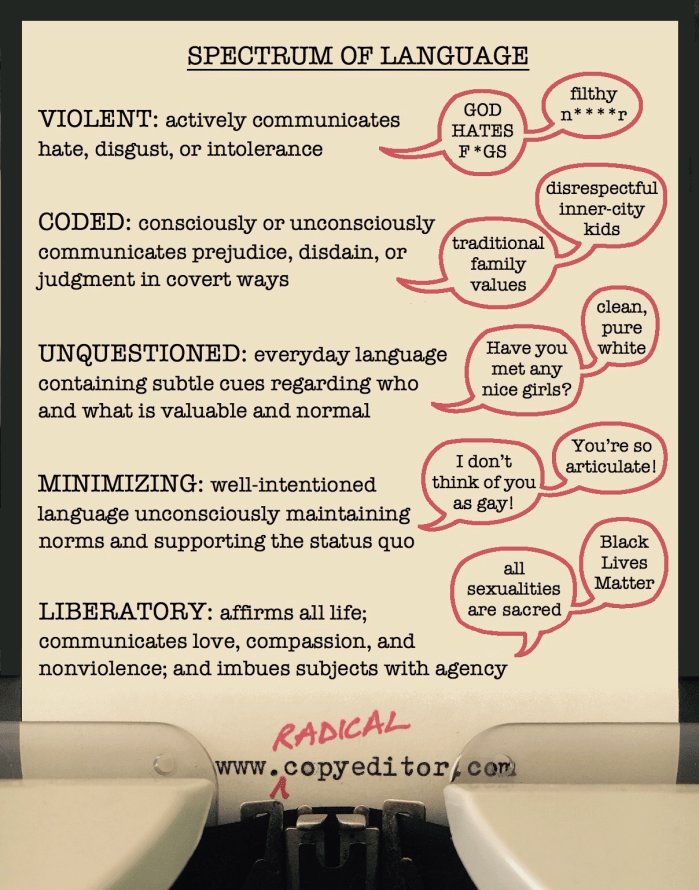

I find it helpful to think of language not as correct or incorrect, good or bad, neutral or biased, but instead as a spectrum from violent to liberatory. The spectrum of language, as I conceptualize it, has five points: violent, coded, unquestioned, minimizing, and liberatory.

Violent language is pretty easy to spot, because it actively communicates hate, disgust, and intolerance. It’s slurs and hate speech.

Coded language is what happens when violent language goes underground. It consciously or unconsciously communicates prejudice, disdain, or judgment in covert ways. Coded language shows up a lot in politics. It’s the dog whistle, it’s phrases like “traditional family values” that on their face might look neutral, but those who are targeted by this language are really clear what’s actually being communicated.

The vast majority of language is unquestioned language that carries subtle and not-so-subtle cues about who and what is most valuable and “normal.” It’s the way stereotypes and expectations and values get baked into everyday speech in ways that most of us never question, like associating the word “white” with positive concepts (white knight, white lie, whitelist, etc.) and the word “black” with negative concepts (black mark, black-hearted, blacklist, etc.).

Minimizing language is well-intentioned but unconsciously maintains oppressive norms. It’s the back-handed compliment, like “you’re so articulate!,” which communicates that it’s a surprise that the person in question would be articulate. Minimizing language also shows up in colorblind approaches that deny difference, or talking about what’s “fair” rather than what’s equitable, or claiming that naming differences is what causes division, rather than systems of oppression.

Finally, there’s liberatory language, which affirms all life; communicates compassion, love, and nonviolence; and imbues subjects with agency.

As before, when I say liberation, what I mean is freedom from violence. The goal of liberation is to eradicate all forms of violence, and one way we can do that is through how we use words. We can either describe and reaffirm a status quo that treats some people as less important, less valuable, and less human, or we can describe and help create a world in which all people are equally valued.

So when we talk about the power of language to cause harm, we need to be clear that the majority of harm caused by language is not caused by actively violent language like slurs or hate speech. The vast majority of harm is caused by the accumulation of unquestioned language. Racism, sexism, ableism, classism, and other oppressions are perpetuated through everyday language that describes what’s real and true, over and over and over, and thus dictates—and limits—how we understand each other, ourselves, and the world.

Using language consciously and anti-oppressively is rooted in care, not correctness. Conscious communication is a lifelong practice, not a checklist of good and bad words. It’s not about censoring or restricting our words, it’s about expanding them, freeing ourselves from oppressive constructs and limiting ways of making meaning. It’s about attending to context and honoring and valuing the full diversity of humanity. It’s about turning toward life, and using words to describe and help create the world we want to live in.

In her absolutely incredible lecture upon receiving the 1993 Nobel Prize in Literature, Toni Morrison said, “We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.” As you receive the gifts of community and conversation today among colleagues and comrades, as you consider what it means and what it requires to publish in a diverse world, my greatest hope is to inspire you to do language. Do it with curiosity. Do it with joy. Do it in ways that help create the world you want to live in. Most of all, do it with care.

Questions? Quarrels? Things to add? Comment below! Want to ask a radical copyeditor something? Contact me! Was this piece helpful to you? Consider making a donation!

This post was made possible by my Patreon community, which supports me in being able to do in-depth research and writing on important topics related to the power of language.

More posts you might like:

Your post was engaging. Language is an addictive subject and very relevant to our lives.

I have only just started studying languages after starting no longer in paid employment.

LikeLike

WOW, just WOW. LOVED this! So powerful, and so poetically written!

LikeLike

I was an editor professionally for 35 years, and I have been a lifelong progressive activist, and your post moved me to tears. I only wish I had had the patience, the discipline, and the clarity to have written something like this myself. I wholeheartedly made every effort to practice the kind of radical editing you describe, making conscious choices about which rules to observe, choosing a language of care, and using language in the service of liberation. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

PS: when I decided to call my business “Book Midwifery,” my well-meaning but old-fashioned dad suggested “book doctor” or “book surgeon,” because these words brought greater prestige. Needless to say, I stood with my original choice.

LikeLike