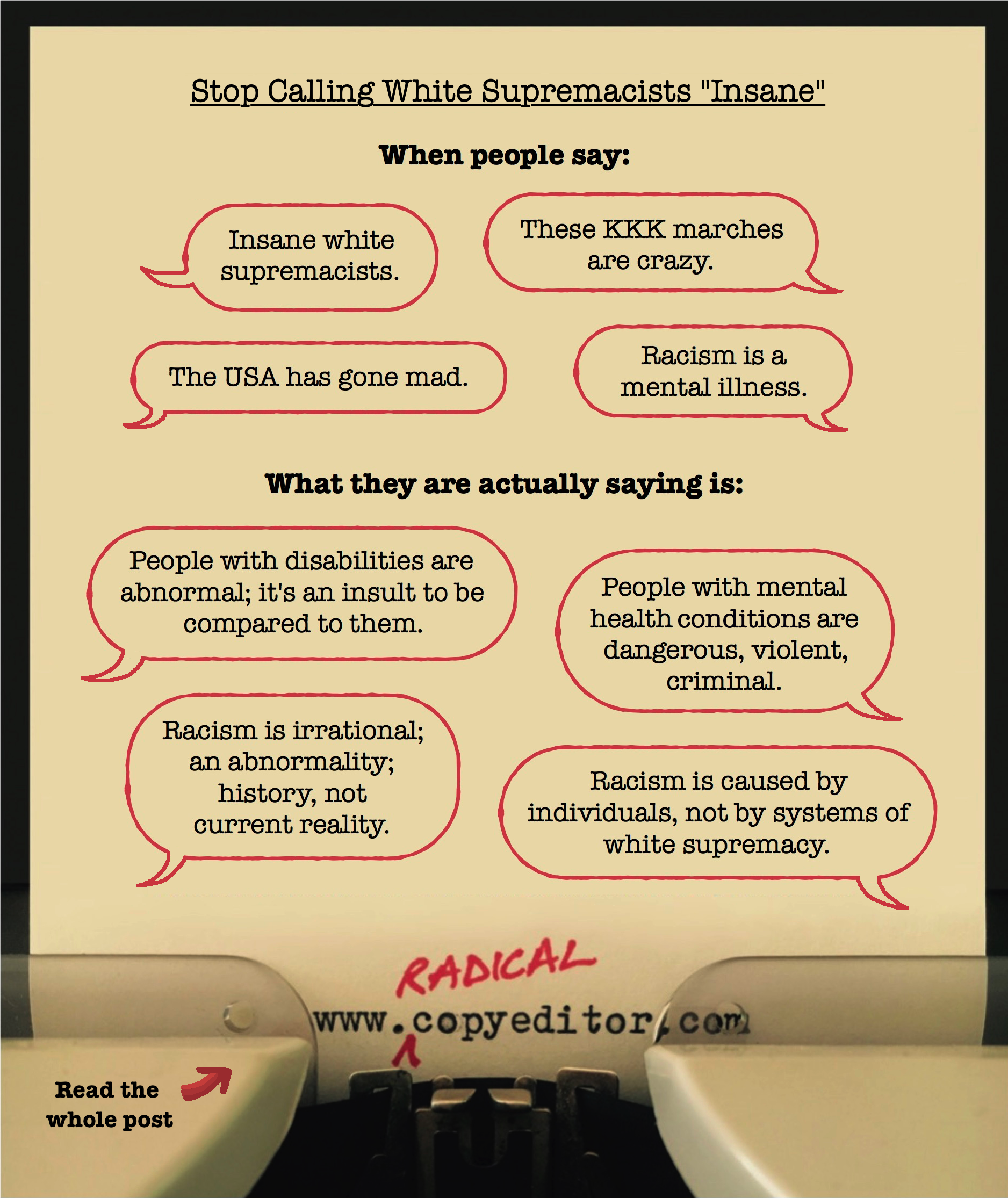

As white supremacists march in cities across the country this month, inciting terror and violence, a lot of people are calling such people “crazy,” “insane,” or “mentally ill.” Beyond the well-documented fact that white lawbreakers are often described by the media in markedly different ways from those who are people of color, calling racism a “mental illness” has got to stop. Here’s why.

1. Calling white supremacists “insane” further stigmatizes people with actual mental health conditions.

After white supremacist Dylann Roof massacred nine worshippers at a historically Black church in June 2015 in the stated hopes of igniting a race war, Kim Sauder (@crippledscholar) posed the following hypothetical question on Twitter: “How can mental illness be used to humanize white perpetrators of mass violence but dehumanize peaceful people with an actual diagnosis?”

Calling white supremacists “insane” or “crazy” treats disability as an inherently negative thing and buys into the myth that having a mental health condition makes a person dangerous, violent, or criminal.

Daniel Bader, a Canadian psychotherapist and blogger at Bipolar Village, writes about what it means when the language of mental health is used in disparaging ways:

The message is, “you’re a bad person, because you’re like a mentally ill person.” That’s not just insulting to [the] target; it’s insulting to every person with mental illnesses in the world. … These terms and associations have become so ingrained in everyday speech, that it’s just become a part of how we conceive of the word: mental illness is scary, weird, and dangerous. … So long as people believe that it is shameful for people to have a mental disability, it will be an insult to “accuse” someone of having a mental disability.

Despite widespread public belief to the contrary, having a mental health condition does not, in and of itself, make a person more likely to be violent or dangerous—ironically, it actually makes one more likely to be the victim of violence. In a 2011 article in Scientific American, Hal Arkowitz and Scott Lilienfeld discuss the fact that drug abuse is a much more likely predictor of violent behavior, pointing to the importance of access to mental health treatment and care, rather than policing and incarceration.

Yet people with disabilities are disproportionately policed and incarcerated. In “The Mass Incarceration of People with Disabilities,” Rebecca Vallas discusses how the United States traded mass institutionalization for mass incarceration when the widespread closure of state-run psychiatric hospitals in the second half of the twentieth century was not accompanied by an investment in community-based alternatives. People with disabilities are also disproportionately subjected to police brutality—one study estimated that 33–50% of all those killed by law enforcement are people with disabilities—and the experiences of people with disabilities behind bars are horrific, often including being illegally deprived of medical care and subjected to mistreatment by staff.

2. Calling white supremacists “insane” dismisses those who perpetuate racism as irrational rogue actors—but racism is a perfectly rational outgrowth of white supremacy culture.

The language of mental health conditions should never be used to dismiss people as being unworthy of being taken seriously, with words like crazy and insane being used as synonyms for irrational and wrong—but that’s exactly what’s going on when people label racism a “mental illness” or call white supremacists “crazy” or “insane.”

Not only does such language further stigmatize people who actually have mental health conditions, but the underlying premise that racism is irrational is also utterly incorrect. If your entire world—from parents to textbooks to media to law—teaches that white is synonymous with normal and American and that people of color are inherently criminal, of course you are going to end up thinking and acting in prejudiced ways.

For almost fifty years, various professionals—many of whom are people of color—have unsuccessfully petitioned the American Psychiatric Association to add racism to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The APA’s reasons for rejecting such proposals are equal parts telling and chilling: In order for racism to be considered a disorder, it must deviate from normative behavior—but racism is ubiquitous, not deviant.

Journalist Arthur Chu called it like it is:

The reason a certain kind of person loves talking about “mental illness” is to draw attention to the big bold scary exceptional crimes and treat them as exceptions. It’s to distract from the fact that the worst crimes in history were committed by people just doing their jobs—cops enforcing the law, soldiers following orders, bureaucrats signing paperwork. That if we define “sanity” as going along to get along with what’s “normal” in the society around you, then for most of history the sane thing has been to aid and abet monstrous evil.

Racist actions are dangerous, immoral, and disturbing to many—but they are not irrational or exceptional, and white supremacists are not inherently mentally unwell.

3. Calling white supremacists “insane” furthers the myth that racism is an abnormality or a historical artifact.

There is a powerful temptation within the United States to pretend that racism is dead and gone, that it was solved with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and proved by the election of a Black president and that in light of all of this, any presence of racism is an abnormality given the rosy egalitarian ideals of the U.S. Constitution.

This mythology is a lie that keeps those under its pull from grappling with the truth that racism is a foundational element of U.S. culture. When the Constitution was written, Black people were not considered people and the Indigenous peoples of this continent were being slaughtered and swindled out of their land. Today, there are more Black people under the control of the criminal injustice system than were enslaved in 1850, Indigenous peoples experience some of the worst health outcomes among U.S. ethnic groups, and the current president ran on a campaign of building a wall to keep out allegedly inherently criminal Latinx people.

In 1984, scholar Jennifer Hochschild wrote:

Racism is not simply an excrescence on a fundamentally healthy liberal democratic body. … Liberal democracy and racism in the U.S. are historically, even inherently, reinforcing; American society as we know it exists only because of its foundation in racially based slavery, and it thrives only because racial discrimination continues. The apparent anomaly is an actual symbiosis.

More recently, journalist Julia Craven succinctly stated:

Racism is not a mental illness. Unlike actual mental illnesses, it is taught and instilled. Mental illness was not the state policy of South Carolina, or any state for that matter, for hundreds of years—racism was.

Racism is not an abnormality or a historical artifact. It is a foundational and current reality of U.S. culture.

4. Calling white supremacists “insane” squarely puts the focus of racism on individual people, not larger systems.

Arguably the other most enduring and problematic myth about racism is the idea that racism can be defined as simple animus toward someone of another race and can be measured by individual prejudiced actions.

Calling white supremacists insane buys into this mythology by focusing on individuals instead of the systems that produced those individuals, and shifting responsibility for racism from the culture as a whole to individual, isolated racists.

Christopher Petrella and Justin Gomer have pointed out that conceptualizing racism as a “disease,” a “mental illness,” or a form of “deviant behavior” is a way of painting racial inequity as “simply the sum of the actions of individual bigots,” leading to the idea that “racial justice can be achieved by ‘curing’ those individuals.” It is dangerous to presume that racism can be eliminated by dealing with a few “bad apples,” because individual actors are not the perpetrators of racism—white supremacy culture is.

Kim Sauder writes about how labeling white supremacists as insane functions to absolve the average white person, and society as a whole, from responsibility:

No one really believes that expressions of racism are inherently insane, it is just a convenient excuse to avoid forcing us to look within. [White people] can continue to claim that these kinds of actions have nothing to do with white people as a whole.

Racism is not the result of individuals, it’s the result of the larger system of white supremacy culture that leaves its mark on everyone within it—and makes us all complicit. Racial justice can only be achieved by changing this larger system, not quashing individual racist actors.

5. Describing racism as a “mental illness” keeps the focus on white people, rather than the people of color who actually suffer the truly disabling effects of racism.

One of the most disturbing side effects of labeling white supremacists “insane” is the way in which doing so inadvertently gives the impression that such people are operating under the influence of a malady that they can’t control.

As Julia Craven put it:

Assuming actions grounded in racial biases are irrational not only neutralizes their impact, it also paints the perpetrator as a victim. Black people, on the other hand, do suffer actual mental health issues due to racism. … Racism isn’t a mental illness, but the psychological, emotional and physical effects on those who experience it are very real.

Furthermore, this re-centering of white people in the conversation about racism invisibilizes the long and disturbing history of people of color actually being diagnosed with mental health conditions in ways that were purely racist.

Scholar Jonathan Metzl provides a chilling take on this history in his book The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia Became a Black Disease. He describes how, in the 1850s, white U.S. psychiatrists invented the mental disorders “drapetomania”—defined by Louisiana surgeon and psychologist Dr. Samuel A. Cartwright as “the disease causing slaves to run away”—and “dysaesthesia aethiopis,” which manifested as “disrespect for the master’s property” and could be “cured” by brutal whippings. Writes Metzl: “Even at the turn of the twentieth century, leading academic psychiatrists shamefully claimed that Negroes were psychologically unfit for freedom.”

Metzl’s book (excerpted here) focuses on the racialization of schizophrenia diagnoses. The disease affects people of all ethnic backgrounds at similar rates, yet a 2005 study showed that Black men are diagnosed with it four times as often as white people. Metzl illustrates how this trend began in the 1960s and ’70s, as the very definition of the disease shifted in ways that painted Black men as “criminally insane.” He uncovered hospital charts that “diagnosed” Black men as schizophrenic in part because of their connections to the civil rights movement and listed symptoms that included being paranoid or delusional about being persecuted for being Black.

This legacy continues today. The intersections of mental health, disability, and race are profound, and labeling white supremacists “insane” obscures these intersections. So when you see or hear someone using this language, be a radical copyeditor and help them understand why doing so is harmful.

Want to learn more about how to fight ableism through your language choices? Check out this solid take by Lindsay Holmes on why it’s important to stop using mental health terminology as metaphors, and this simple graphic from Upworthy with great alternative word choices.

*Note: In researching this piece, I was frustrated by the number of authors who have written about how problematic it is to call racism a “mental illness” using an anti-racist lens but no disability justice lens. If you know of more authors in the field of disability justice who have written on this specific topic, please share!

More posts you might like:

Hey, Alex!, I am Nana in Alaska, Rhonda A.’s friend/sister. I sure sent your new, brilliantly done post far and wide. Much educating in store here in AK for perspective of creating enlightenment of harm on harm with equating mental illness with these so called, ‘white supremacists’, those who seem to be exposing themselves; a scum rising to the top of the fermenting crock of pickles! Planet-wide, we are seeing the draconian element self-igniting.

Had you given much thought to the potential of George Soros fomenting this particular and other incidents of domestic discord via funding to pay organizers and influencing the way the resulting conversation (and thus the language) would be structured by creating a ‘battle’ of forces at play?

LikeLike

Thank you for this article. Would you be open to sharing more of the articles you read when researching this piece? I’m curious about the racial justice articles you found.

LikeLike

Hi Will — all of the articles that I found most helpful are linked in the piece itself. But a google search will easily turn up more — in particular, there were a lot of pieces published from the racial justice angle in the wake of Dylann Roof’s crime and sentencing.

LikeLike