Language isn’t correct or incorrect, it’s a spectrum from violent to liberatory. When I strive to use language in ways that are inclusive of the full diversity of human experience, it’s not about being correct or avoiding offense. It’s about creating the opportunity for perspectives that have historically been squelched to shine. It’s about empowerment, and agency, and collective care. It’s about liberation.

The idea that avoiding “offending” people is the primary goal of sensitive language is inherently minimizing—it automatically calls up the idea that being offended is a result of being either overcritical or oversensitive, nothing more. It also squarely puts the burden of how language is experienced on the people who are hearing or reading it. It says that if you are offended by particular language, it’s your fault, not the speaker or author’s.

Focusing on “offense” doesn’t allow for the possibility that a person could be negatively impacted by careless or hostile language—the worst thing they can experience is being offended. Everything about this line of reasoning is dismissive in nature. The solution for “being offended” is not for responsibility to be taken by the person who caused the offense, it’s for the listening or reader to simply stop being offended—“toughen up,” recognize that no offense was intended, “grow up.”

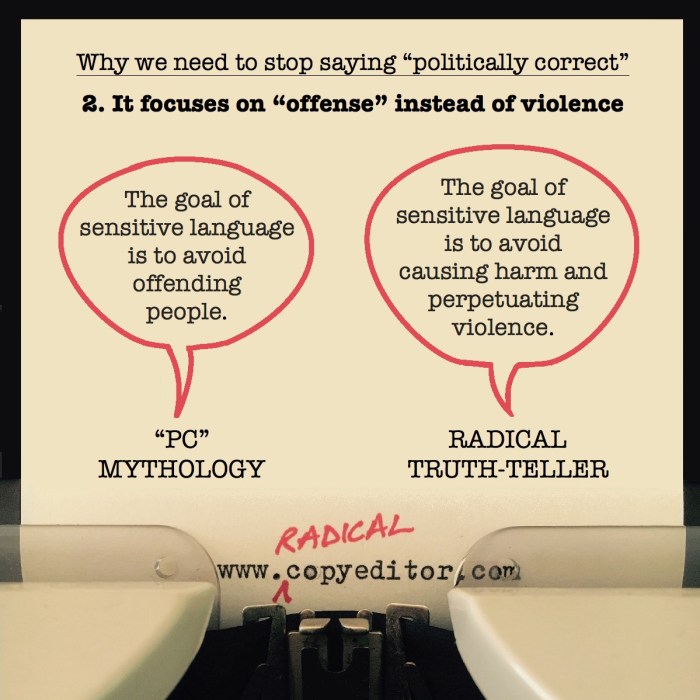

Avoiding offense is not the point of inclusive and sensitive language. The real issue is that certain language causes harm and perpetuates violence, not that it “offends” people.

Here’s an example of what I mean. Over the course of decades, heterosexuality has been privileged as the only valid form of sexuality and everyone who is not straight has been painted as perverted and deviant. When language confirms this, not just once but over and over again, by teachers, media, religious leaders, judges, politicians, and all kinds of other people, it causes real harm. Its effects on people who are not straight are every bit as real as physical violence.

So if someone asks two women, “So, who’s the man in your relationship?” those words build on a century of oppressive language that has kept non-heterosexual people marginalized. The two women might react with anger, frustration, tears, stony silence, dejection, or resignation. Are they offended? Sure, but that’s not the point. The point is they’ve been hurt, and their pain has deep roots.

Perhaps the person didn’t mean to hurt anyone. After all, many people who ask that question are trying to be insulting, but many others are genuinely curious and have no idea how gender roles play out in same-sex relationships.

But the fact remains that the words this person used have caused harm. They are a reminder that same-sex relationships are not “normal” according to the mainstream—as well as the fact that women can’t be understood as full human beings in their own right without any reference or relationship to men. And these words have potentially called to mind every similar slight these two women have experienced over the course of their lives.

Using sensitive language isn’t about protecting yourself from angry, offended people. It’s not about finding the right words to gloss over or obscure your biases and prejudices while leaving them intact and unquestioned. Using sensitive language is about caring for the people who interact with your words.

The term “politically correct” does nothing to support this truth. Instead, it denies the fact that words can cause harm and blames people who are hurt for being unjustly “offended.”

It also communicates that people care about language solely for the sake of following a set of politically defined rules about it, rather than for the sake of the people behind the words.

Read on:

Go back:

[Description of featured image above: Reason #2 for why we need to stop saying “politically correct”: it focuses on “offense” instead of violence. “PC” mythology speech bubble says: “The goal of sensitive language is to avoid offending people.” Radical truth-teller speech bubble says: “The goal of sensitive language is to avoid causing harm and perpetuating violence.”]

Hi, I recently (today actually) came across your blog and I’m highly intrigued by its content. Thanks for writing about these kinds of topics! There are so many harmful ways in which language is used, which people are unaware of because of “normalisation” of terms throughout time. I don’t think words themselves are inherently harmful, yet the meaning they have and ideas they spread are huge and very powerful. It would be nonsense to deny the harm words can bring, and with it the strength sensitive language has. It still surprises me how many people are unaware of these meanings or talk their impact down, whether purposely or not. I, as well, didn’t know the history of “politic correctness” and I’m glad I found out. I didn’t like the way it was used, but wasn’t entirely sure why. Again, thanks for writing these kinds of articles!

That said, I was also wondering if you would be okay with me writing a poem or lyrics based upon this article? I would very much like to use it as inspiration, but I might use some terms you used as well. By no means I intend to copy anything, but I still wanted to ask for permission.

LikeLike

Thanks, Katrin! I’m glad you find my blog helpful! And thanks for asking permission to use this piece as inspiration for a poem or lyrics—you absolutely may. If it’s possible to provide credit and a link back somewhere, I would appreciate that.

LikeLike

Credit as well as a link will definitely be placed in the post. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person