Today I made a third major update to The Radical Copyeditor’s Style Guide for Writing About Transgender People to add four sections on how to avoid writing or talking about trans people in ways that are invalidating or otherwise harmful. (Remember that context is everything, and that all trans people have a right to describe themselves in whatever language feels best to them.)

I also updated section 1.4 and the note that follows it to reflect better language that has emerged for instances when you want to be clear that when you say trans you aren’t referring only to trans women and men but also non-binary people, as well as the recent trend in trans communities to perceive trans and transgender as having separate meanings.

See below for these new sections or click through for the updated style guide.

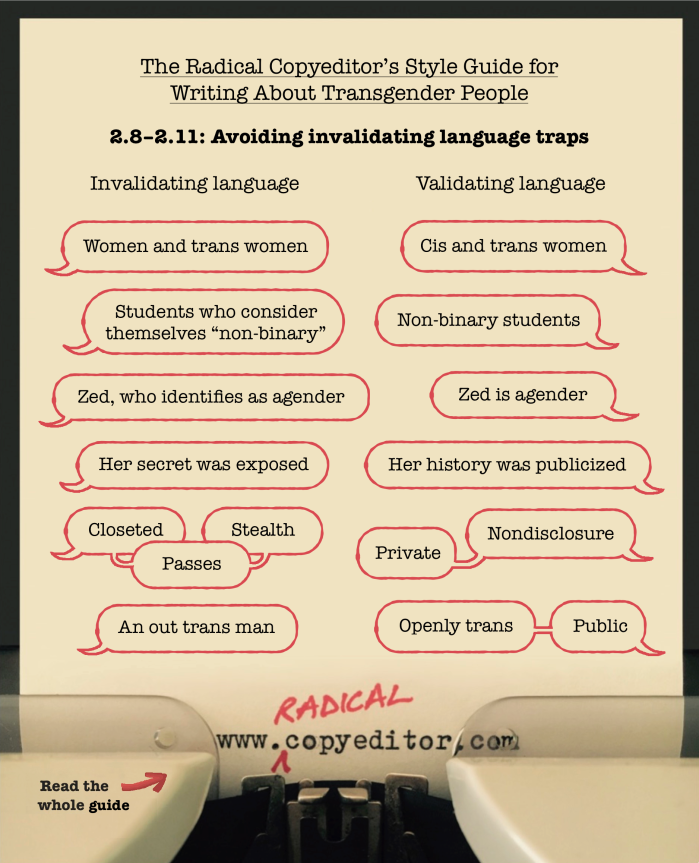

2.8. Affirm that trans women are women, trans men are men, and non-binary people are non-binary.

Use: all women, including trans women; cis and trans men; cisgender people

Use: Maria, a woman from Nogales; non-binary students; Zed is an agender young adult

Avoid: women and trans women; normal people; real men; biological women

Avoid: Nogales resident Maria, who identifies as a woman; students who consider themselves “non-binary”; Zed identifies as agender

A consistent way that trans people’s identities are invalidated is when trans women and men are treated separately, linguistically, than cisgender women and men and when language is used to describe trans people’s genders, names, or pronouns that undermines them or calls them into question. Ashley Dejean’s article “How Journalists Fail Trans People” powerfully speaks to this.

As an example, a cis woman would never be described with the language “Mary Beth identifies as a woman” (one would just say “Mary Beth is a woman”), so using this language for a trans woman marks her as different and undermines her gender. Another example of invalidating language treatment is the use of “scare quotes” to set off the words trans folks use to describe ourselves.

2.9. Don’t sensationalize or nonconsensually disclose a trans person’s gender history.

For the majority of modern history, mainstream forces have treated (and written about) trans and gender nonconforming people as freakish, deviant, mentally unwell, and criminal. The media has been the primary source of sensationalizing and nonconsensually disclosed information about us. This context is vitally important.

Many trans people simply want to be able to live their lives as men, women, or non-binary people. If a person’s gender history isn’t relevant, don’t mention it (unless they want you to). And never disclose details related to a trans person’s gender history (such as their birth name or the sex they were assigned at birth) without consent. Doing so is at best gossip and at worse violence, and communicates that the person isn’t really who they are presenting themself as today.

2.10. Never use language that paints trans people as deceptive for living as our authentic selves.

Avoid: her secret was discovered; he disguised himself as a woman; she fooled everyone; no one knew the truth; the lie was exposed

Not only is there a long and storied history of trans people being perceived as deceitful simply for living our lives and being ourselves, but the choice to not disclose details of one’s past or anatomy has been used as justification for brutality toward and murder of trans folks (see: the infamous “trans panic” defense), so it is extra important to avoid any language that gives the impression that a trans person who chooses to keep details of their gender history private is lying, deceptive, or false, as Gwendolyn Ann Smith has powerfully written about.

Instead of secret or truth, try history or past. Instead of closeted or disguised, try private or nondisclosure. See also 2.3. regarding passing and stealth.

⇒ A note on out and closeted: Coming out is the process of becoming aware of your authentic identity and/or sharing that identity with others. A trans man who has transitioned is fully out as a man; whether or not he chooses to share his gender history with others is irrelevant. Being closeted means denying one’s identity to oneself and/or others, but if one’s identity is man and one is living life fully as a man, one is out. When a person shares that they have a history of gender transition, that is a disclosure, not an act of coming out.

2.11. Don’t perpetuate or validate trans-exclusionary hate or prejudice.

This should go without saying, but just in case it’s not clear, there aren’t two balanced sides to the story of whether or not trans people have the right to exist in public, in the words of Laverne Cox. Anyone writing about trans people has a moral obligation to do no harm, and this includes not perpetuating or validating perspectives that are harmful to trans people. For example, in discussing anti-trans legislation, writers often repeat prejudiced language (such as “bathroom bill”) or try to present “both sides” in ways that ultimately lend credence to hate, intolerance, or ignorance. Don’t do this. Trans lives and dignity are not up for debate.

⇒ A note on “TERF”: TERF stands for “trans-exclusionary radical feminist” and refers to people (most of whom are older, white, cis women) who believe that trans women are actually men. As a (feminist) radical copyeditor, I reject the idea that there is anything radical or feminist about this violent perspective, so I don’t use the term “TERF.”

Read the whole guide: “The Radical Copyeditor’s Style Guide for Writing About Transgender People”

If you find my work useful, please consider making a donation to support me!

Thank you, Alex!

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike

Would you mind if I printed this out for my classroom?

LikeLike

Thank you for asking! You may do that. I actually have a PDF version of the full guide, linked from that page, if that would be useful for your purposes. Check it out here: https://alexkapitan.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/trans-style-guide_rev-july-2018.pdf

LikeLike

How do you consider the aesthetic of “people first” language, which contradicts some of your recommendations? That is, “students who are non-binary” is preferred over “non-binary students”, and “women who are cis and trans” is preferred over “cis and trans women”?

LikeLike

As it happens, I’ve written a whole other piece on the incredibly flawed concept of “person-first language” as a language rule. I strongly encourage you to read it: https://radicalcopyeditor.com/2017/07/03/person-centered-language/

I’m curious to know whom, exactly, the awkward constructions you offered are “preferred” by. I’m also curious to know what these constructions meaningfully accomplish, in your opinion. As you’ll see when you read the piece linked above, a better language guideline is “person-centered language,” which puts the actual person first, not necessarily the word person, and practices the truth that all people should be treated as the first and foremost experts on themselves.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I like your list, except for the “students who consider themselves non binary vs non binary student”. As an educator, we are taught to put the student first, so we say “student with disability”, “student w autism” “student who is gifted and talented”. For us, we honor/validate everyone as a person first, label second. Perhaps it would be better “student who is non binary “.

Now if you wanted to say non binary “person” then I probably wouldn’t have noticed.

LikeLike

I’m no uncritical champion of “person-first language”; I had only thought it was the most widely practised way to refer to groups of people with an attempt to be sensitive and inoffensive. There is, obviously (as you clearly show in your linked article), no consensus like I had imagined.

I think Ladau really hits the nail on the head: “Person-first language essentially buys into the stigma it claims to be fighting.” I, for instance, have no qualms about being referred to as a cheese lover, or a brown-haired person, so perhaps it’s only because of my internalized homophobia that I prefer not to be called a gay or a gay person—if I was as comfortable with my orientation as I am with my love of cheese or hair colour, you’d expect me to be comfortable with parallel grammar constructions.

Thank you for introducing me to the more sensitive and contemporary practice of “person-centred language”.

PS I’m writing from Canada. Should I be following Canadian grammar convention as a submitter, or should I follow the lead of the publisher?

LikeLike

Well said, Christopher! I’m glad my piece was helpful to you. In terms of your question about Canadian style conventions, it’s sort of up to you and depends on what publication you are writing for.

Lauralee, if you haven’t read the piece I link to in my comment above on “person-first language,” please do. Your “student-first language” convention is the exact same thing and comes with the same problems. It would decidedly not be better to say “student who is non-binary” instead of “non-binary student.” Your desire to honor everyone as “a person first, label second” is a good one, but it’s important to consider which terms are labels and which terms are self-identities. A label is a term that one person or group applies to another person or group without their input. A self-identity is a term that one person or group uses to describe something important or essential about themselves. For example, “handicapped” is a label. So it’s crummy to refer to folks as “the handicapped” because it uses a label as a stand-in for their very personhood. But when someone self-identifies as disabled, or autistic, or female/girl, or Black, the best way to honor/validate them as a person first is to honor/validate the language they use to describe themself. It is not honoring or validating them to “correct” or “improve on” their self-identity language. Someone who identifies as a disabled, autistic, Black girl is a disabled, autistic, Black girl, not a student with a disability who has autism spectrum disorder, is African American, and is female. I hope this makes sense.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“It would decidedly not be better to say ‘student who is non-binary’ instead of ‘non-binary student.’

Unless of course the student preferred “student who is non-binary”, no?

LikeLike

“Person-first” language is still widely used by people to self-identify. Sometimes an author using “person-first” language is validating and respecting a subject’s choice to self-identify that way.

So sometimes “person-first” language is also “person-centred” language. It’s not fair to write off all “person-first” language as “incorrect”. Those personal choices shouldn’t be invalidated.

LikeLike

Yes, of course, Christopher. Thanks for the clarification on both counts.

Re: “student who is…”, I only meant that the phrase “student who is non-binary” is not in and of itself an improvement over “non-binary student.” If an individual person preferred the former then of course that’s what would be best in that case, although I’ve yet to encounter that preference within non-binary circles.

Re: person-first language, when I say that it’s a flawed rule, I’m only talking about it as a written-in-stone rule, which is unfortunately the way many people practice it. I am definitely not saying it’s incorrect to ever put the word person first. You are absolutely right that the most validating thing to do is to respect a subject’s choice to self-identify in whichever way works best for them. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also to note. Non-Binary is also descriptive of an Enby.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment, Celeste. “Enby” is a word that evolved from “non-binary,” when non-binary started being abbreviated as NB and then NB started being spelled out phonetically as enby. So “non-binary” and “enby” essentially refer to the same group of people. Not all non-binary folks use the word enby or describe themselves as enbies.

LikeLike

This is excellent! Just a note re: the acronym TERF – it was coined by trans inclusive radical feminists to differentiate themselves from a vocal subsection of the community that they disapproved of. I agree that TERFs aren’t really radical or pro-women, but the whole point of the term was to say that radical feminism should be trans inclusive by default.

I’m not sure it’s useful to avoid the term because “TERFs aren’t really radical or feminists” – I think it’s better to say “Germaine Greer’s feminism is trash” rather than “Germaine Greer’s feminism isn’t really feminism”. Does that make sense?

Cristan Williams has written a very good article on the subject:

http://www.cristanwilliams.com/b/2016/05/08/radical-inclusion-recounting-the-trans-inclusive-history-of-radical-feminism/

LikeLike